How does alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency affect the liver?

Pulmonologists frequently test for alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency in patients with emphysema, especially those with early onset emphysema, emphysema associated with lighter smoking histories, or those with lower lobe-predominant bronchiectasis. The mechanism by which having alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency might predispose to emphysema is clear. But it was less intuitive why deficiency of this enzyme could cause chronic liver disease.

Alpha-1 antitrypsin is a protease inhibitor, specifically targeting and deactivating neutrophil elastase. It is made in the liver and then travels to the lungs, where it helps protect them from excessive neutrophil elastase activity. In essence, alpha-1 antitrypsin prevents excessive tissue breakdown in the lungs and airways.

Those with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency make less of this enzyme, or the alpha-1 anti-trypsin they do make is dysfunctional, depending on the mutated allele they have. A normal genotype contains two normal M alleles and is therefore called MM. The most common mutated genotype is called ZZ, but there are others as well. Many have interesting names, including Mmalton or Mmineralsprings and QOgranite falls, likely based on where those mutations were discovered. Those who are heterozygous carriers of an abnormal alpha-1 gene are often asymptomatic.

The emphysema and bronchiectasis seen in patients with alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency is due to a loss of elastase inhibition and uncontrolled elastin breakdown in the lungs. Too much elastase activity leads to tissue destruction; when it involves the alveoli and parenchyma, emphysema results. When the airways are involved, you see bronchiectasis.

The mechanism of liver injury is completely different and involves something called toxic gain of function. When alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency affects the lungs, the disease results from a toxic loss of function. The loss of alpha-1-antitrypsin function leads to excessive neutrophil elastase activity and results in lung damage. The initial step in the chain of events is a loss of the normal function of neutrophils. In the liver, the issue is a toxic gain of function.

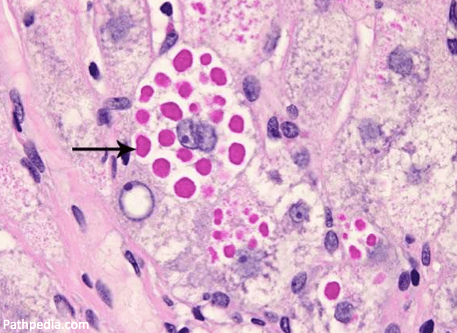

Histologically, liver sections from alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency patients show PAS-positive inclusions or clumps filling the tissue. These clumps are polymerized alpha-1 antitrypsin aggregating in hepatocytes. This accumulation is called a toxic gain of function,” as opposed to the toxic loss of function that leads to emphysema.

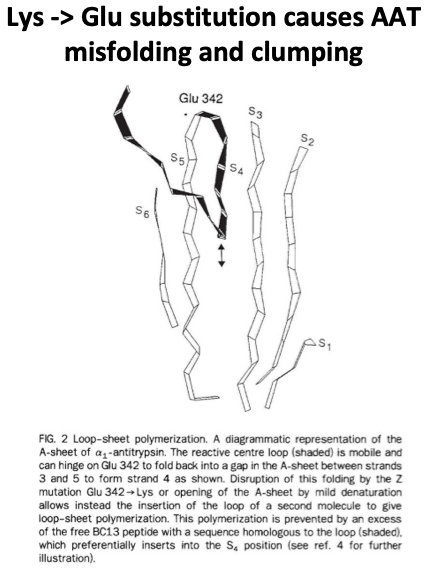

The ZZ genotype provides the best example, as it is the most common mutation in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and has the strongest association with liver disease. In those with the ZZ genotype, there is a crucial amino acid substitution where a lysine is substituted for glutamic acid in a specific hinge point in the structure of the protein. This disrupted hinge point causes protein misfolding, polymerization of the misfolded protein, and accumulation of the abnormal alpha-1 in the endoplasmic reticulum of hepatocytes. These inclusions cause mitochondrial damage leading the injured mitochondria to release reactive oxygen species resulting in hepatocyte damage. This process has been called proteotoxic stress.

The accumulated protein gets “stuck” in the liver and cannot traverse to the lung to prevent neutrophil elastase activity in the lung, leading ultimately to lung tissue breakdown and emphysema.

Unsurprising, a “null” genotype, where no alpha-1-antitrypsin protein is produced at all, leads to severe emphysema but no liver disease. This demonstrates that protein production is necessary for liver disease. A function of gained.

The treatment of lung and liver manifestations of alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency follows from these mechanisms of injury. In patients with severe enzyme deficiency and significant lung disease, supplemental alpha-1 protein via IV infusion can be used. This therapeutically replaces the missing enzymes, i.e., the toxic loss of function. Because liver disease results from toxic gain of function and results from inclusion clumping right after the protein is produced, infusions, unfortunately, do not impact liver injury.

One of the main predictors of more advanced liver disease and progression to cirrhosis from alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency appears to be obesity. And this appears to be a bidirectional relationship with heterozygosity a risk factor for the progression of fatty liver disease to NASH cirrhosis. In a 2020 retrospective study of liver explants from NASH cirrhosis patients, 20% had one alpha-1 Z mutation.

While patients who are heterozygotes have essentially normal serum levels of alpha-1 antitrypsin the chronic inflammatory injury resulting from NASH interferes with autophagy and the removal of the abnormal alpha-1 antitrypsin being produced. This allows it to remain in the liver and contribute to fatty liver disease progression.

Take Home Points

- The liver disease seen in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency results from misfolding and clumping of abnormal protein in hepatocytes, which injures mitochondria.

- This is an example of toxic gain of function, which differs from the toxic loss of function in seen in emphysema related to alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency.

- There is a bidirectional link between liver disease in alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and obesity, with obesity being a prime risk factor for alpha-1 liver disease progression to cirrhosis and heterozygosity for alpha-1 seeming to be a risk factor for the progression of fatty liver disease to NASH cirrhosis.

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

Listen to the episode

Link to associated tweetorial

Credits & Citation

◾️Episode written by Avi Cooper

◾️Show notes written by Avi Cooper and Tony Breu

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Cooper AZ, Breu AC, Abrams HR. Including the liver. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. April 19, 2023.

This episode is sponsored by BetterHelp! You can give online therapy a try at betterhelp.com/CLINICIANS.

Image credit: https://www.pathologyoutlines.com/topic/liverAAT.html