Why does it take weeks for the radiographic evidence of pneumonia to clear?

Early in medical training, many of us are told that it takes weeks for the radiographic infiltrate to resolve after a bout of pneumonia. This is the sort of statement many accept without question. But it is worth wondering what is in that infiltrate at week 2 or 4 or 6. If the patient is better, why isn’t the chest x-ray (CXR)?

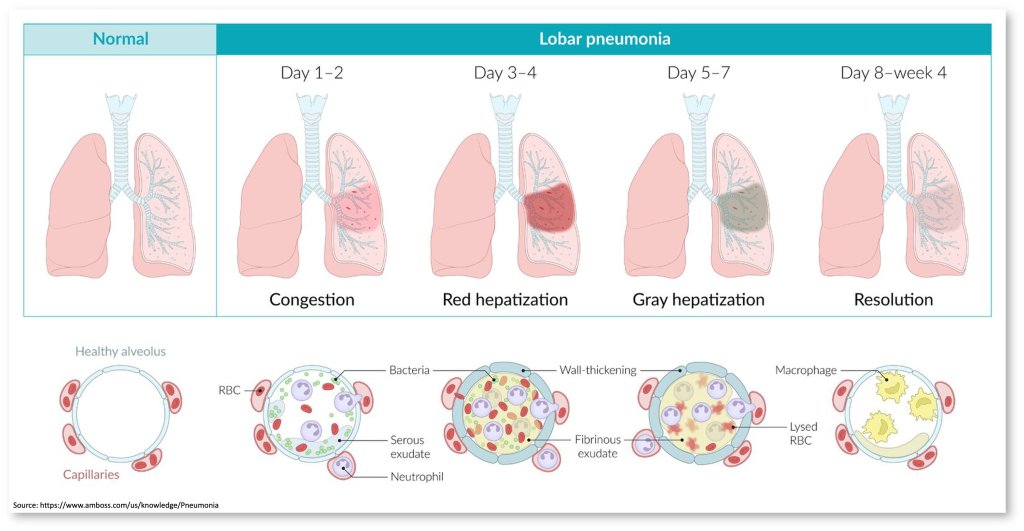

Early in pneumonia, neutrophils are drawn to the alveoli to attend to invading bacteria. This happens at the behest of cytokines, including IL-8. The result is a CXR infiltrate containing these neutrophils with engulfed bacteria along with edema, fibrin, RBCs, and desquamated epithelial cells. It’s an inflammatory infiltrate. Basically, it is pus.

This is typically what you see over the first four days of a pneumonia. The fact that we see this inflammatory infiltrate helps explain why corticosteroids might help in severe cases. It’s often the over-exuberant inflammatory response that leads to severe illness. Steroids help to dampen this a touch.

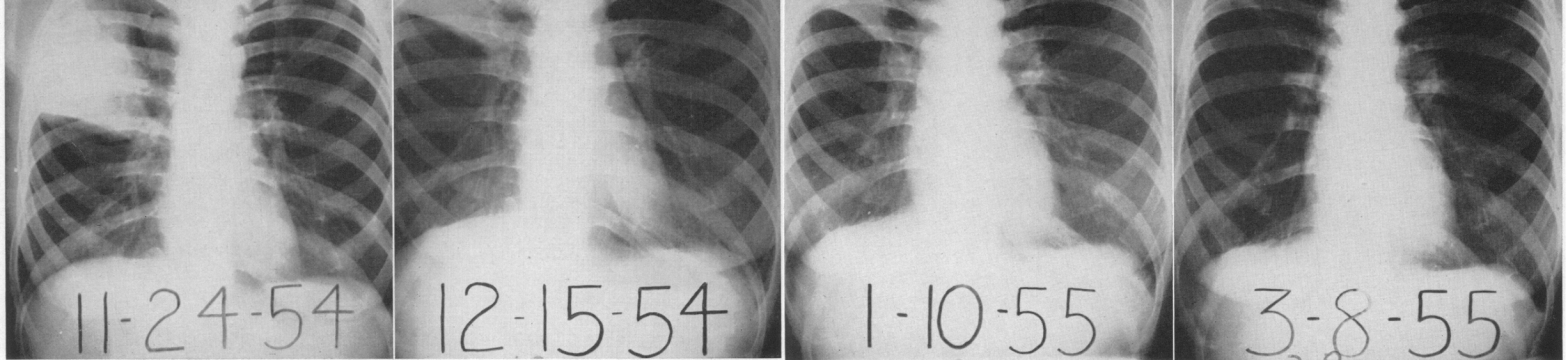

Around day 5, bacteria have been removed, and neutrophils are no longer the main immune cell. And yet we still see an infiltrate on CXR. In fact, early studies suggest that consolidations remain for up to 6-8 weeks.

This is partly why we can stop antibiotics long before the infiltrate has completely resolved. Our bodies immune response addresses the bacteria present in the lung. And clearly antibiotics accelerate this process. Decades ago, we learned that bacteria quickly disappear from sputum once antibiotics are administered. Within a couple of days. This is part of the basis for short-duration regimens in pneumonia: if the bacteria are quickly killed, long courses are not required.

There is even a 1970 study where a single intramuscular dose of long-acting penicillin or a single day’s therapy with oral penicillin were compared with standard oral and injection therapies for the treatment of lobar pneumonia. Those receiving just one dose did just as well as those receiving longer courses.

There’s one other interesting observation that follows from the rapid bacterial killing. This leads to reduced production of exogenous pyrogens. This may explain the equally swift resolution of fever which is just 2-3 days in pneumonia.

During the period of recovery from pneumonia, when an infiltrate is still present but bacteria and neutrophils are no longer present, the macrophages is the main immune cell seen. These macrophages are engaging in something called efferocytosis. Efferocytosis is the removal of apoptotic bodies by macrophages. This might include neutrophils with engulfed bacteria. In essence, the immune system is in hyperdrive over the first 1-4 days. Neutrophils and cytokines create a enormous immune response. This leads to the intended outcome of bacterial killing. But there is also tissue issue. This mess needs to be cleaned up. Macrophages spend weeks cleaning up a mess that neutrophils created in just a few days.

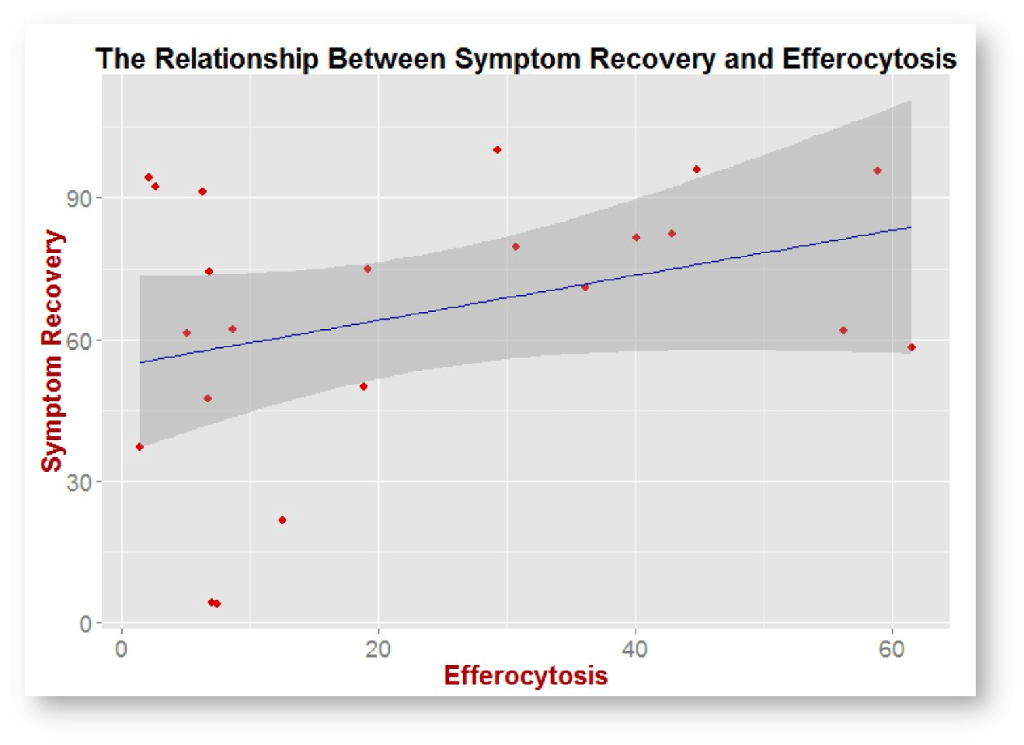

Amazingly, apoptotic cells increase the exposure of phosphatidylserine. This is recognized as an “eat-me” signal by macrophages. Efferocytosis prevents secondary necrosis and the release of proinflammatory molecules from apoptotic bodies. Again, we want the inflammatory response early on. But as we sterilize the lung we need to ratchet things back. Unsurprisingly. more effective efferocytosis has been linked to improved symptomatic recovery after pneumonia.

A number of things affect the efficiency of efferocytosis. Smoking, for one, impairs the process and is associated with prolonged recovery after pneumonia. And there is some data that glucocorticoids and statins augment efferocytosis. Simvastatin has been tested as an adjunctive treatment for CAP with no benefit seem. But what’s interesting is that these studies only gave the drug for 4 days. There aren’t any trials where statins have been adminsitred to aid with the resolution of infiltrates.

Some bacteria have learned a way to circumvent efferocytosis. Klebsiella pneumoniae impedes efferocytosis by preventing phosphatidylserine expression on the surface of apoptotic neutrophils. Other organisms, including salmonella, Mycobacgerium tuberculossi, and legionella inhibit apoptosis, thereby reducing the ability for macrophages to engage in efferocytosis. This many explain the longer time needed for radiographic resolution based on the bacteria. In one study published in Thorax in 1984, radiographic resolution was fastest with mycoplasma pneumonia. Psittacosis and non-bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia cleared at an intermediate rate. Legionnionella and pneumococcal pneumonia with bacteremia had the slowest period of resolution. At 12 weeks, just under half of patients with legionella pneumonia still had an infiltrate.

Efferocytosis isn’t just about clearance of pneumonia. It also plays a role in other conditions characterized by chronic infiltrates. These include idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and cystic fibrosis.

Take Home Points

- The initial infiltrate in pneumonia contains neutrophils and bacteria.

- The later infiltrate – seen up to weeks after clinical stability – is largely made up of macrophages engaging in efferocytosis, cleaning up apoptotic debris.

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

Listen to the episode

https://directory.libsyn.com/episode/index/id/27010419

Link to associated tweetorial

Credits & Citation

◾️Episode and show notes written by Tony Breu

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Breu AC, Cooper AZ, Abrams HR. Slow to Resolve. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. May 31, 2023.

Image credit: Kirby, W. M., Waddington, W. S., & Francis, B. F. (1957). Differentiation of right-upper-lobe pneumonia from bronchogenic carcinoma. New England Journal of Medicine, 256(18), 828-833.