Why doesn’t factor 12 deficiency cause bleeding?

In July 1953, freight brakeman John Hageman’s doctors faced a scenario that might feel familiar to anyone who has ever done preoperative medicine consults. Hageman had planned to undergo a partial gastrectomy for peptic ulcer disease, but his preoperative tests showed a prolonged clotting time. In the 1950s, we knew about other diseases with prolonged clotting times; hemophilia in particular, which at the time referred to what we now know as hemophilia A (Factor 8 deficiency) and hemophilia B (then known as Christmas disease and now known as Factor 9 deficiency). But Oscar Ratnoff and Joan Colopy, two scientists who investigated the case further, found a few things that made it clear Hageman didn’t have either condition. So why did he have a prolonged clotting time without any bleeding symptoms?

First, Ratnoff and Colopy noted a few tests and observations that distinguished Hageman’s condition from hemophilia. First, Hageman’s clotting time improved with the addition of even small amounts of blood from people with factor 8 or factor 9 deficiencies, indicating that neither was the missing piece. If the missing step in forming a clot was either factor 8 or factor 9, then that blood would not have corrected the issue. Second, Hageman’s apparent condition did not act like any of these classic deficiency states. And last, perhaps most importantly, John Hageman wasn’t bleeding! He was an asymptomatic (at least as related to bleeding/clotting) 37-year-old man being assessed in a preoperative clinic. His bleeding time was normal, and he had previously undergone a tonsillectomy, a dental extraction, and a traumatic hand injury as a kid, all without bleeding. This is not the experience of someone with hemophilia.

Fortunately, this asymptomatic lab test ultimately did not keep Hageman from getting his surgery. In 1954, the same year Ratnoff and Colopy published their observations on Hageman and two other people with the same condition, he underwent a partial gastrectomy and gastrojejunostomy without excessive bleeding or wound healing complications. However, he was transfused pre-emptively during and after the case.

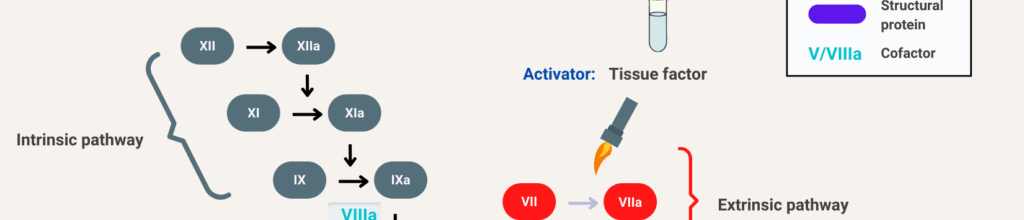

To understand how a prolonged bleeding time might not place one at risk for bleeding, it helps to compare it with severe hemophilia A. Those with hemophilia have a near-complete lack of factor 8. Because factor 8 is a component of the intrinsic coagulation cascade, their labs will show a prolonged partial thromboplastin time (PTT) with a normal prothrombin time (PT) and thrombin time (TT). These tests allow one to ‘localize the lesion’ to the intrinsic clotting cascade.

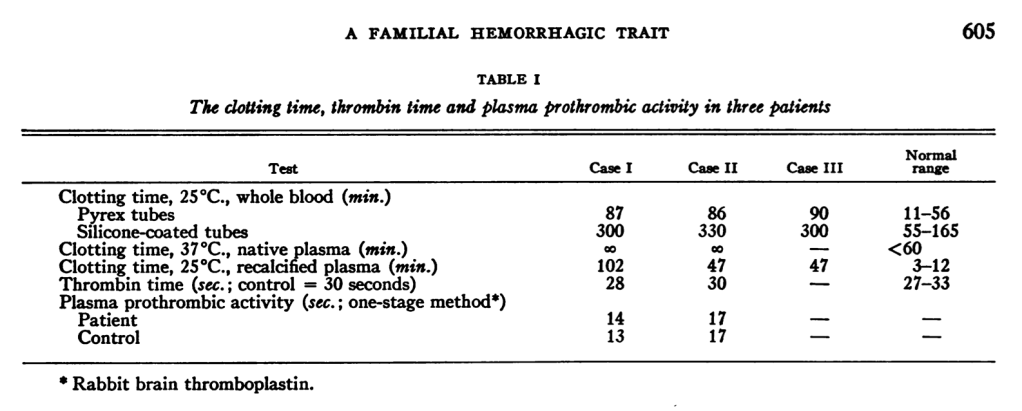

As with hemophilia A, Hageman’s PT and TT were normal, and mixing his plasma with plasma that contained any missing factor corrected the problem. So it looked like classic hemophilia. But when Ratnoff and Colopy performed other tests, they found unusual results. The first thing they did was to measure the overall clotting time. This meant putting whole blood in a tube and measuring how long it takes to form a clot at a given temperature. When they did this with Hageman’s specimen, it took 87 minutes for whole blood to clot in a glass tube. To examine whether this was a platelet issue or a plasma issue, they separated the two and ran the test again. When they did that, the plasma in a glass tube absolutely did not clot, for at least 5 hours.

Two other strange things happened. Rafnoff and Colopy wondered whether the glass might be playing a role. So they added 100 mg of crushed-up glass to a tube. When they did this, Hageman’s sample did clot, but instead of the 87 minutes, it took 182 minutes. Then, with 500 mg of crushed-up glass, it took 144 to clot. Finally, they found that diluting the whole mixture could also improve clotting time, down to 113 minutes.

What does all of this mean? Because the addition of normal plasma corrected the bleeding time, we can conclude that Hageman had a factor deficiency. But adding glass and diluting are not consistent with a factor deficiency. So there must be something more to it. Ratnoff and Colopy concluded that “the defect was at an early stage in the clotting process,” with the idea that perhaps all this occurred somewhere in the clotting process that then later affected what they then knew as anti-hemophilia factor, now known as factor 8. This idea of “early” and “late” stages in the clotting process led to the modern understanding of the coagulation cascade.

We now know that John Hageman lacked factor 12. And Hageman remains the namesake of the Hageman trait, also known as factor 12 deficiency. But why didn’t Hageman bleed?

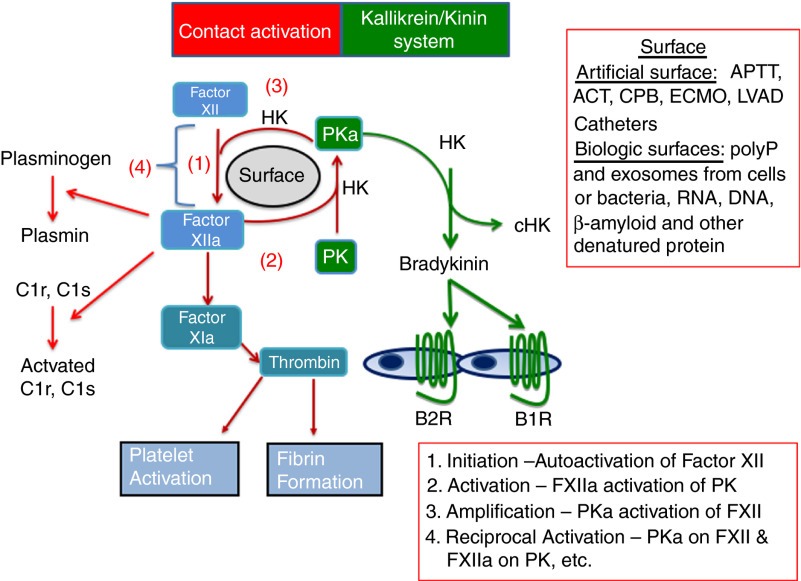

Turns out that factor 12 is an enzyme that can autoactivate itself after contact with artificial surfaces, like glass or bacteria, and can then start a clot by activating factor 11. Factor 12 does not appear to be involved in regular day-to-day clotting in the human body. Instead, clots can initiate through the extrinsic pathway by exposure of tissue factor. Then the intrinsic cascade can propagate downstream of factor 12, with thrombin activating factor 11a as a loop that essentially bypasses 12. So, when Hageman had his tonsils out, those alternate ways of starting the cascade would have served him just fine. In fact, Hageman himself died of a pulmonary embolism, which occurred after he had a boxcar accident and fractured his pelvis, requiring multiple weeks of immobility. Going back to the original experiments, adding all that glass might provide tons of surface area to allow clotting to begin and maximize the use of any factor 12 in the sample.

If factor 12 doesn’t play a significant role in clotting, what does it do? This is a research question that has now been studied for about 70 years. In 2016, the Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis published a review that began with “Factor XII is a mysterious plasma protein without a clear physiologic function. It was identified as a clotting factor, but has no clear role in hemostasis.” The contemporary understanding is that factor 12 plays a role in inflammation and may also participate in wound healing through multiple mechanisms.

And factor 12 deficiency is not uncommon. Although we don’t know the true prevalence because most people are asymptomatic. There is a wide range of prevalence estimates, but in one study of healthy blood donors, 1 in 300 had severe factor 12 deficiency, and another 6 in 300 had moderate deficiency.

In the modern era, factor 12 may have more to teach us. Just a few months before we recorded this episode, Tem Bendapudi published a detailed characterization of clotting in both humans and mice that are heterozygous for factor 12. They found that in a sample of over 700,000 people from the United Kingdom and the United States, being a factor 12 carrier was associated with a significantly decreased risk of venous thromboembolism (HR = 0.648) without an increased risk of bleeding or sepsis. This would challenge how we typically think of inheritance for clotting factor deficiencies and point to the existence of a distinct ‘haploinsufficient‘ state — just another way that John Hageman continues to teach us about the world of clotting.

Take Home Points

- Hageman factor deficiency, also known as factor 12 deficiency, is an asymptomatic condition characterized by a prolonged PTT but no increased risk of bleeding.

- Factor 12 helps start coagulation in vitro because it’s able to activate on the glass surfaces of the test tube, but in vivo we have other ways to initiate clotting.

- Early studies on factor 12 laid the foundation for the modern coagulation cascade, and very recent studies suggest that there may be factor 12 haploinsufficient states, which would challenge how we commonly think about coagulation factor inheritance.

Sponsor

This episode was sponsored by FIGS. FIGS is offering 15% off your first purchase. Just go to wearfigs.com and use the code FIGSRX at checkout.

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Hannah Abrams

◾️Show notes written by Hannah Abrams and Tony Breu

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Abrams HR, Cooper AZ, Buonomo G, Manna, M, Breu AC. The Forgotten Factor. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. January 7, 2026.

Image Credit: https://www.thebloodproject.com/ufaq/what-is-the-clotting-cascade/