Why don’t we all get heparin-induced thrombocytopenia?

Way back in episode 59, we discussed why heparin, a commonly-used anticoagulant in the hospital, can cause mild hyperkalemia. The more widely-known side effect of heparin, though, is heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), of which there are two types: Type 1 (non-immune mediated) and Type 2 (immune-mediated). If a hospitalized patient suddenly has low platelets and is being anti-coagulated, HIT is always on the differential. However, this raises a question: Since our bodies actually produce heparin endogenously, why don’t we all get HIT?

First, let’s review the history of heparin. In 1916, Jay McLean was a second-year medical student at Johns Hopkins who, as one story goes, approached William Howell because he had written McLean’s favorite physiology textbook. McLean joined Howell on a project to isolate procoagulant substances in the body, initially in the brain and later in the liver. However, McLean ended up identifying phospholipids with anticoagulant properties In 1918, Howell and L. Emmett Holt Jr. (another medical student) isolated a phospholipid molecule they called “heparin” as it was initially isolated from dog liver cells (“Hepar” is from the Greek for liver). Several years later, Howell isolated a anti-coagulant polysaccharide that he also called heparin, and is the heparin that is still used today. There was (and still is) controversy surrounding McLean’s contribution to heparin’s discovery, which he claimed equal credit for, but others argue that while his research may have kickstarted the discovery process, he never actually isolated heparin as we know it.

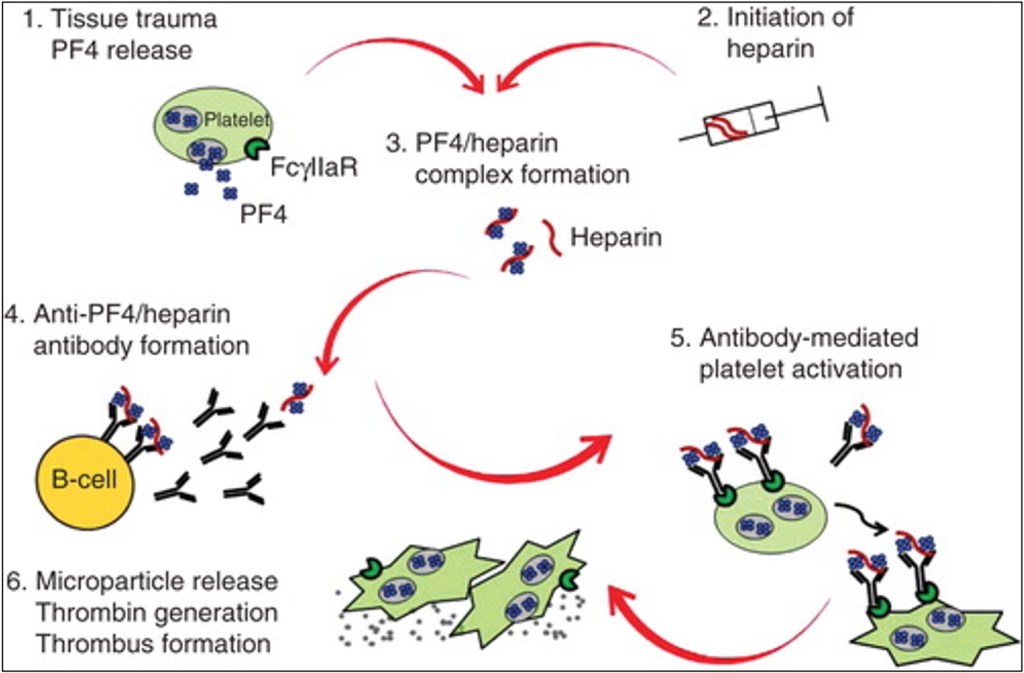

It took more than a decade for heparin to be used in clinical trials, but by the 1930’s it was being used to treat not only thrombotic conditions but also endocarditis, cancer and other conditions. Along with reports of its clinical effectiveness, reports of thrombocytopenia quickly appeared. However, it wasn’t until the 1960s and 1970s that the concept of an immune-mediated thrombocytopenia after heparin exposure emerged. I. A 1994 study elucidated the exact mechanism of HIT Type 2: Platelet-factor 4 (PF4) complexes with heparin, which the body produces antibodies against. The PF4/heparin/antibody complexes bind to platelet receptors, leading to their activation and aggregation (which is why a complete blood count shows thrombocytopenia). Once activated, platelets release procoagulant microparticles, leading to thrombin generation and, ironically, increased risk of venous and arterial thrombosis.

What we learned in the last two paragraphs seems to be at odds with each other. Heparin is produced endogenously, but can also induce an immune reaction, which we usually think of exogenous substances doing. Why doesn’t everyone walk around with HIT all day then?

The answer is simple: We just don’t have that much heparin produced naturally in our body. Studies from the 1960s suggest that the normal concentration of heparin in the body is about 0.1 to 0.2 U/mL. When used as a drug, we aim for values five to ten times this. The majority of our endogenous heparin is actually contained within mast cells (immune cells best known for driving allergic reactions) and gets released at sites of injury. Since many invertebrates without coagulation systems also produce heparin, it’s unclear whether our heparin is even used as an anti-coagulant, and just has some unknown immune function (which could still be some type of local anti-coagulation).

It’s true that around 5% of the population walks around with antibodies to the PF4/heparin complex, even without prior exposure to therapeutic-dose heparin. The vast majority of these people are asymptomatic (density testing can be used to quantify exactly how much antibody is present and then if they have any effect on platelet aggregation). However, does that mean that a select few can get spontaneous HIT? Sort of. There are patients who get an acute thrombocytopenia from PF4 immune complexes. However, heparin doesn’t drive that reaction – knee surgery does. Yes, you read that right.

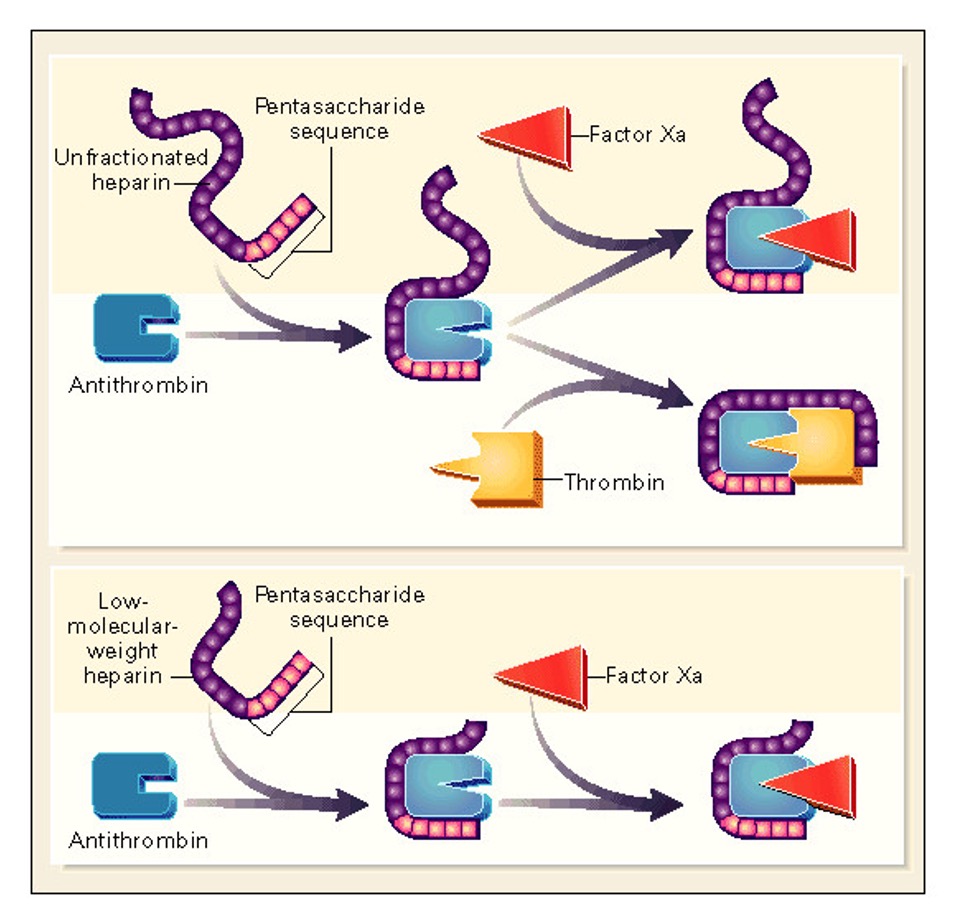

To understand how exactly this happens, we have to think about why “real” HIT occurs in the first place. Heparin is a very negatively-charged molecule, which allows it to bind to and potentiate the highly-positive antithrombin of the coagulation cascade. Unfortunately, PF4 is also highly positive, which is why heparin forms complexes with it. “Unfractionated” pharmaceutical heparin comes a jumble of glycosaminoglycan molecules of different sizes, while “fractionated” or “low molecular weight” heparin has been processed to make them uniform. Due to it’s heterogenous binding sites, unfractionated heparin can stick more easily to other molecules, which makes it both a quicker, less-predictable anticoagulant but also more likely to cause HIT than the fractionated version.

Knee connective tissue is full of glycosaminoglycans, including hyaluronic acid and chondroitin sulfate, which are all negatively charged. What else is a negatively-charged glycosaminoglycan? Heparin. The theory is that when someone undergoes major knee surgery like a total arthroplasty, the bloodstream is flooded with these negatively-charged molecules, which bind PF4 and induce a HIT-like immune response. A similar phenomenon can be seen during viral infections as the bloodstream is inundated with viral DNA and RNA (which may be why some COVID-19 patients are so hypercoagulable).

Despite the risk of HIT, heparin is likely to remain an essential drug due to its potent anti-coagulant effects and ease of administration, especially in the hospital. Unfractionated heparin is actually still derived from animals, previously cows and now pigs, mostly from China given its large-scale pork production. One hopes that the current tariffs won’t limit access to this lifesaving medication.

Take Home Points

- HIT results from the formation of complexes between heparin and platelet factor 4.

- Although humans produce their own heparin, it circulates at very low concentrations, leaving us protected against spontaneous HIT.

- Spontaneous HIT does occur, though it is a result of non-heparin negatively charged molecules that also have the ability to bind PF4.

Listen to the episode!

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Tony Breu

◾️Show notes written by Tony Breu and Giancarlo Buonomo

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Breu AC, Abrams HR, Cooper AZ, Buonomo G. The HITS Keep Coming. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. May 28th, 2025.

Image Credit: Shutterstock

I love your podcast.I have never witnessed such deep knowledge with simple explanation.Thanks for all the efforts.Please keep going

LikeLike