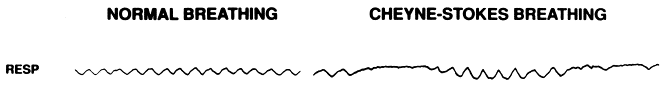

Most of us have seen a patient with Cheyne-Stokes respirations, whether we know it or not. This pattern of breathing consists of a continuous cycle of hyperpnea (i.e., fast and deep breathing) and apnea. And the cycle just goes back and forth between these two patterns.

Cheyne-Stokes is a very old clinical sign. Hippocrates (or the Hippocratic authors) is thought to have first described it around 400 BC. The patient’s name was Philiscus and he was observed to have respirations that were “like that of a person recollecting himself, rare and large.” This pattern matches well the two phases of Cheyne-Stokes breathing.

Enter Cheyne and Stokes

It wasn’t until a few centuries later that the pattern was fully described and named. Below are quotes from John Cheyne and William Stokes, each describing the clinical finding that bear’s their names.

How does it start?

What initiates and perpetuates this breathing pattern and what conditions are associated with it?

Let’s start by answering the second question first. Patients with heart failure, particularly those low ejection fractions, are those typically observed to have Cheyne-Stokes respirations.

And why patients with heart failure. A key point to understand is that chronic hypocapnia (i.e., low blood carbon dioxide levels) is common in patients with advanced heart failure. This may result from chronic congestion leading to stimulation of irritant lung receptors, among other things. Importantly, a 1993 study in the journal Chest found that patients with Cheyne-Stokes respirations consistently had low pCO2 levels. This suggests that chronic hypocapnia is the inciting event.

What’s normal?

Normally, breathing is either volitional automatic or volitional. As you read this, you are using automatic breathing. This is also the case when you sleep. At other times you might intentionally increase or decrease your respiratory rate or depth of breathing.

Automatic breathing is controlled by the aptly named respiratory control center in the medulla in the brainstem.1 It receives input from peripheral chemoreceptor and irritant and stretch receptors in the blood and lung, but also from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pH via central chemoreceptor and adjusts breathing patterns to maintain a steady serum CO2 level. Think of a thermostat in your home adjusting the furnace to a temperature goal.

How is Cheyne-Stokes different?

Remember that patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fracture are predisposed to hypocapnia. Hypocapnia then has a specific effect on the respiratory control center, at least partly from effects on CSF pH. During periods of hypocapnia, CSF pH decreases resulting in less stimulation of central chemoreceptrors. This leads to shallower and less frequent breaths or even apnea. The blood CO2 level at which this occurs is called the apnea threshold.

With severe hypocapnia the blood pH can rise dramatically leading to profound respiratory alkalosis. By crossing an apnea threshold, the low pCO2 shuts this process down and prevents us from voluntarily become too alkalemic.

Patients with chronic hypocapnia tend to live just above their apnea thresholds with respect to CO2. But those with heart failure and reduced ejection fracture the pCO2 levels are often already close to the apnea threshold. This mean that the pCO2 would not have to fall much to drop below this threshold. Once it does, an apnea occurs.

Going back to a normal response, our CO2 thermostat quickly adjusts our respirations and returns our pCO2 back to normal. The key word here is quickly. Changes in pCO2 are normally sensed very rapidly with a resulting change in our breathing. This explains why it is so hard to volitionally hold your breath too long. This apnea results in a rise in pCO2 which quickly triggers us to resume breathing.

A crucial concept to understand is that patients with advanced heart failure and reduced ejection fraction have slower circulation speeds than normal. A 1933 study found the blood of such patients circulates much more slowly compared to those with normal cardiac function. The circulation times were 26 seconds and 15 seconds, respectively. The marked increase in circulation times is felt to result from the decreased cardiac output.

Again, the normal response to the rise in pCO2 during an apnea is to quickly resume normal breathing. But in advanced heart failure the increased circulatory time renders this pCO2-ventilatory relationship unstable. Instead of a rapid response and correction of hypercapnia that occurs under normal circumstances, slower blood flow causes the respiratory control center to not realize that pCO2 levels are rising. The CO2 levels that the brain sees are still below the apnea threshold and so the apnea persists much longer than it should. Eventually the brain senses higher CO2 levels that occurred during the apnea and it reacts by inducing rapid, deep breathing to clear the CO2.

This, of course, means that the brain is always responding to outdated information about pCO2. This leads to constant overcorrection – overcorrection of respiratory acidosis leads to hyperventilation which leads to respiratory alkalosis and apnea. You may see this referred to in the literature as loop gain, which is a concept borrowed from electrical circuitry. And this cycle keeps repeating itself in the Cheyne-Stokes pattern.

Take Home Points

- Cheyne-Stokes respiration is triggered by the combination of chronic hypocapnia and decreased cardiac output

- Chronic hypocapnia leads to apneic episodes. Low cardiac output causes slow circulatory flow and delayed responses to changes in serum CO2

- This results in a cycle of apnea and hyperpnea/tachypnea because of loop gain, as the brainstem’s response to changes in CO2 levels is always lagging behind what’s actually going on in the blood.

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (1.00 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (1.00 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (1.00 hours).

Listen to the episode

https://oembed.libsyn.com/embed?item_id=20477297

Credits & Citation

◾️Episode written by Avi Cooper

◾️Show notes written by Tony Breu and Avi Cooper

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Cooper AZ, Abrams HR, Breu AC. Why does severe heart failure lead to Cheyne-Stokes breathing? The Curious Clinicians Podcast. September 15, 2021

Image credit: https://www.ajconline.org/article/S0002-9149(97)00936-3/fulltext

1In Central Hypoventilation Syndrome (CHS) this autonomic control fails resulting in apnea during sleep. This has been referred to as Ondine’s Curse in reference to the 1938 play Ondine by Jean Giraudoux. In the play, the water-spirit Ondine tells her future husband Hans “I shall be the shoes of your feet … I shall be the breath of your lungs”. Ondine then makes a pact with the King of the Ondines that if Hans ever deceives her he will die. Later, Hans leaves Ondine for his first love Princess Bertha. On Hans and Bertha’s wedding day Hans says to Ondine “all the things my body once did by itself, it does now only by special order … A single moment of inattention and I forget to breathe.” After Hans and Ondine kiss, Hans dies.

Related tweetorial: https://x.com/AvrahamCooperMD/status/1338160033851461634?lang=en