For this episode of the podcast, we explored why metronidazole treats both bacterial and parasitic infections, why it is only effective against anaerobic organisms, and how this relates to the supposed disulfiram-like reaction. Our discussion was based largely on Avi’s tweetorial posted on May 3, 2020.

Bacteria AND Parasites?

Metronidazole was developed in the 1950s to treat the parasite trichomonas and then was used in the 1960s to treat other parasitic infections, like giardia and amoebiasis. Only in the 1970s was it noted to be active against Bacteroides fragilis. It then became widely used as an antibiotic to treat anaerobic bacterial infections.

Metronidazole is interesting in that it treats BOTH bacteria and parasites (trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is another example). It is bactericidal against anaerobic bacteria (includes gram positives and gram negatives) as well as microaerophilic bacterial like Helicobacter pylori. But, it is also used to treat anaerobic parasites like Entamoeba histolytica and giardia.

In a way, metronidazole is a remarkably selective drug, treating only anaerobic organisms.

Pyruvate!

Pyruvate metabolism is key to understanding metronidazole’s mechanism of action. In particular, one must understand the different ways that aerobes and anaerobes metabolize pyruvate.

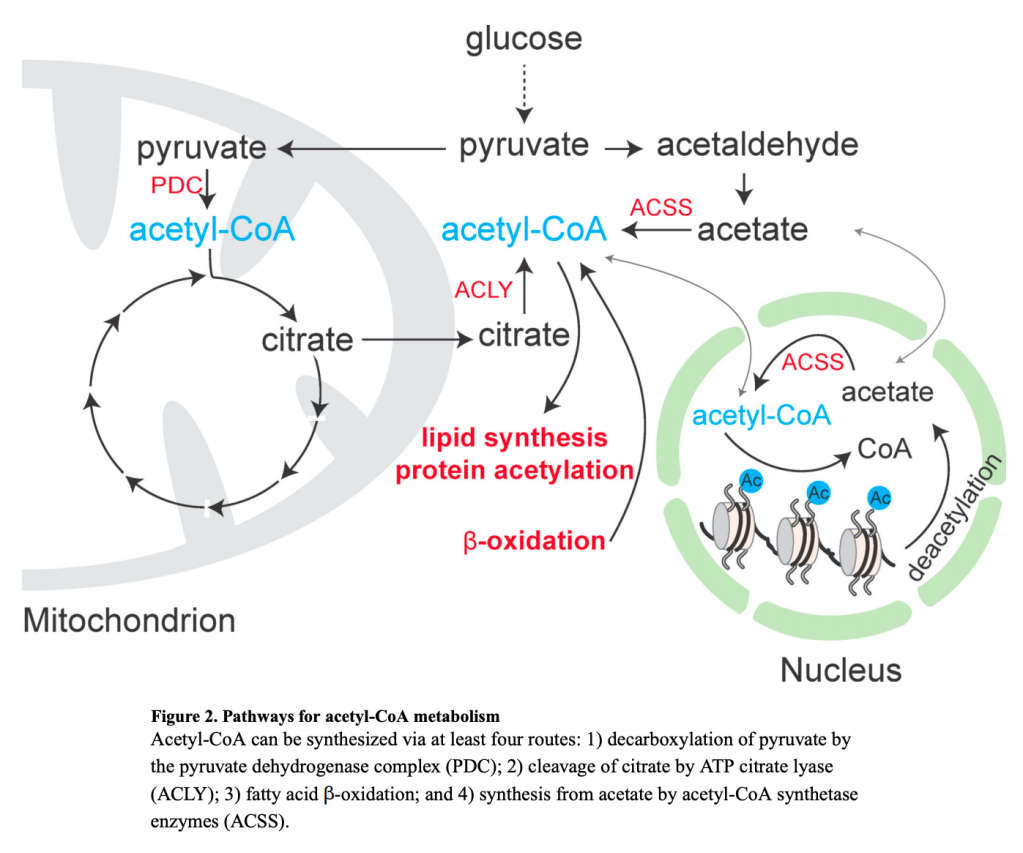

Aerobes (e.g. Homo sapiens or aerobic bacteria) use the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) to convert pyruvate to acetyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA then then goes into the Krebs Cycle and ultimately generates ATP.

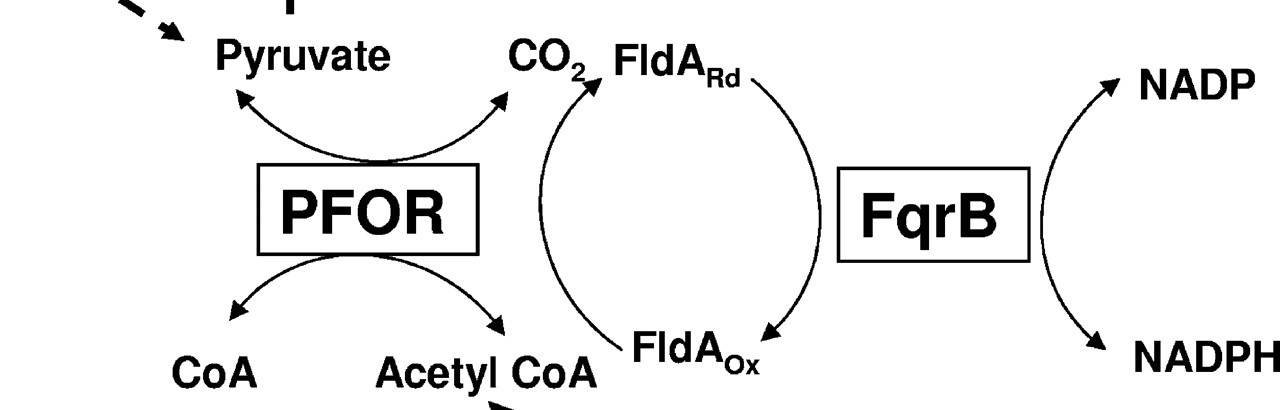

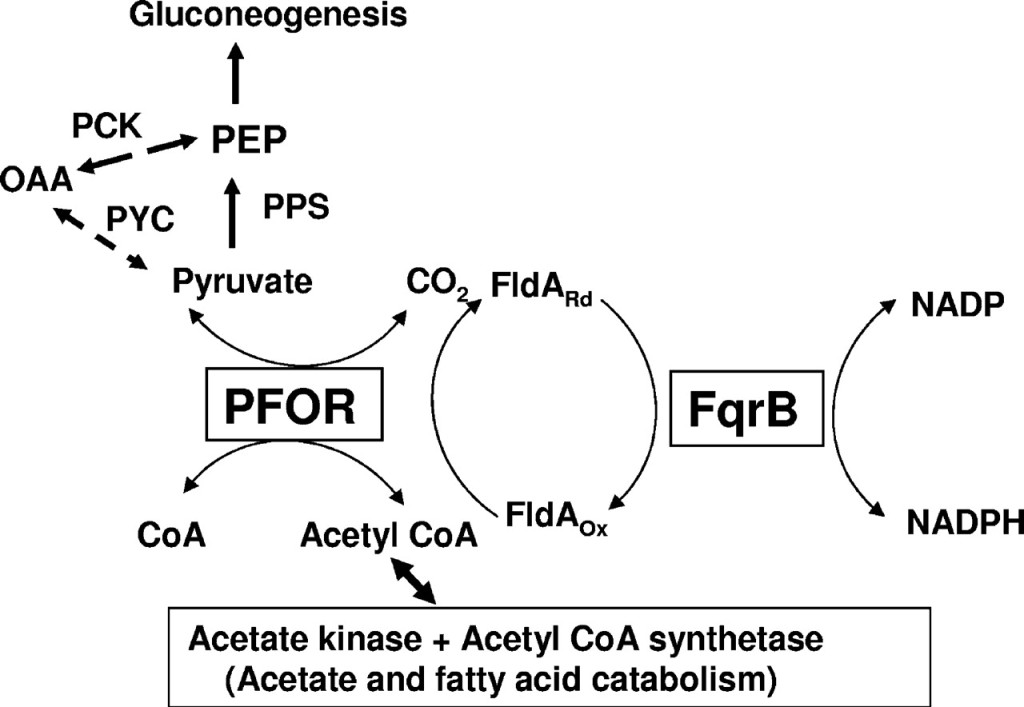

Anaerobic bacteria and parasites have a completely different mechanism for processing pyruvate. They still convert pyruvate to acetyl-CoA but they use a different enzyme called pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PFOR), which catalyzes a red-ox reaction that moves electrons around.

PDC is used by aerobes

PFOR is used by anaerobes

Here’s the key: metronidazole acts as a target for PFOR and gets reduced, effectively activating the drug. Metronidazole then accumulates electrons, forms superoxide anions, damages DNA, and kills the organism. In effect, PFOR converts metronidazole into a DNA-damaging toxin, but only does so in anaerobes that utilize PFOR. This leaves aerobic cells utilizing PDC (e.g., human cells) unaffected.

Disulfiram-like Reaction?

There are case reports that when metronidazole was mixed with alcohol it led to a disulfiram-like reaction, including flushing, nausea/vomiting, and headaches, though the level of evidence of supporting the existence of this association is limited. At the same time, this potential reaction is included as a precaution in the drug insert and is commonly discussed with patients by prescribers.

The actual disulfiram-alcohol reaction is caused by inhibition of hepatic aldehyde dehydrogenase and build up of acetaldehyde after ingestion of alcohol.

Metronidazole doesn’t have this same effect on alcohol dehydrogenase. But, bacteria metabolize acetyl-CoA to acetaldehyde, which is then converted to ethanol (a form of fermentation). Aerobic bacteria are able to run this second reaction in reverse, generating acetaldehyde from ethanol.

An experiment in rats found that combining ethanol and metronidazole led to a spike in acetaldehyde in the rats’ colons. This most likely occurred because metronidazole selectively kills anaerobic bacteria, leaving the aerobic bacteria free to metabolize the ingested alcohol, generating acetaldehyde. Is this the mechanism of the purported disulfiram-like reaction in humans? This isn’t settled.

Radiosensitizer?

If metronidazole’s ability to treat both aerobes and anerobes didn’t amaze you, perhaps the fact that it previously was used as a radiosensitizer for radiotherapy in cancer therapy will.

Experiments done in the 1970s showed that treating hypoxic or anoxic human cells with metronidazole makes them more sensitive to radiation. The mechanism of this isn’t entirely clear but it may be that the metabolic changes in anoxic cells allows metronidazole to undergo the red-ox reaction necessary to activate it, even without PFOR present.

A small randomized clinical trial in the New England Journal of Medicine in 1976 studied the effects of adding metronidazole to a radiotherapy regimen for glioblastoma. They found a longer survival in the metronidazole group, theorizing that that it had made the radiotherapy more effective at killing anoxic tumor cells.

In the 1970s and 1980s metronidazole was actually used clinically as a radiosensitizer! More recent studies showed mixed results and metronidazole is no longer standard of care, but this historical association is pretty cool.

Learning Objectives

- Metronidazole is selectively active against anaerobic bacteria and parasites due to activation by pyruvate:ferredoxin oxidoreductase (PFOR), an enzyme unique to anaerobic organisms.

- Although we think of metronidazole mainly as an antibiotic, it actually was developed in the 1950s and 1960s to treat parasites such as trichomonas and amoebiasis.

- The disulfiram-like reaction may result from selective killing of anaerobic colonic bacteria by metronidazole, allowing aerobic bacteria in the colon to produce acetaldehyde from ingested alcohol.

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (1.00 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (1.00 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (1.00 hours).

Listen to the episode

Credits & Citation

◾️Episode written by Avi Cooper

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

◾️Show notes by Tony Breu and Avi Cooper

Cooper AZ, Abrams HR, Breu AC. Why does metronidazole treat both bacterial and parasitic infections? The Curious Clinicians Podcast. September 30, 2020. https://curiousclinicians.com/2020/09/25/why-does-metronidazole-treat-both-bacterial-and-parasitic-infections/

Image credit https://jb.asm.org/content/189/13/4764/F6