Why do patients with active lupus have a low CRP?

Although the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is typically high in active lupus, C-reactive protein (CRP) is often normal. What’s particularly cool about this finding is that it lends insights into the mechanism of lupus and potentially its cause.

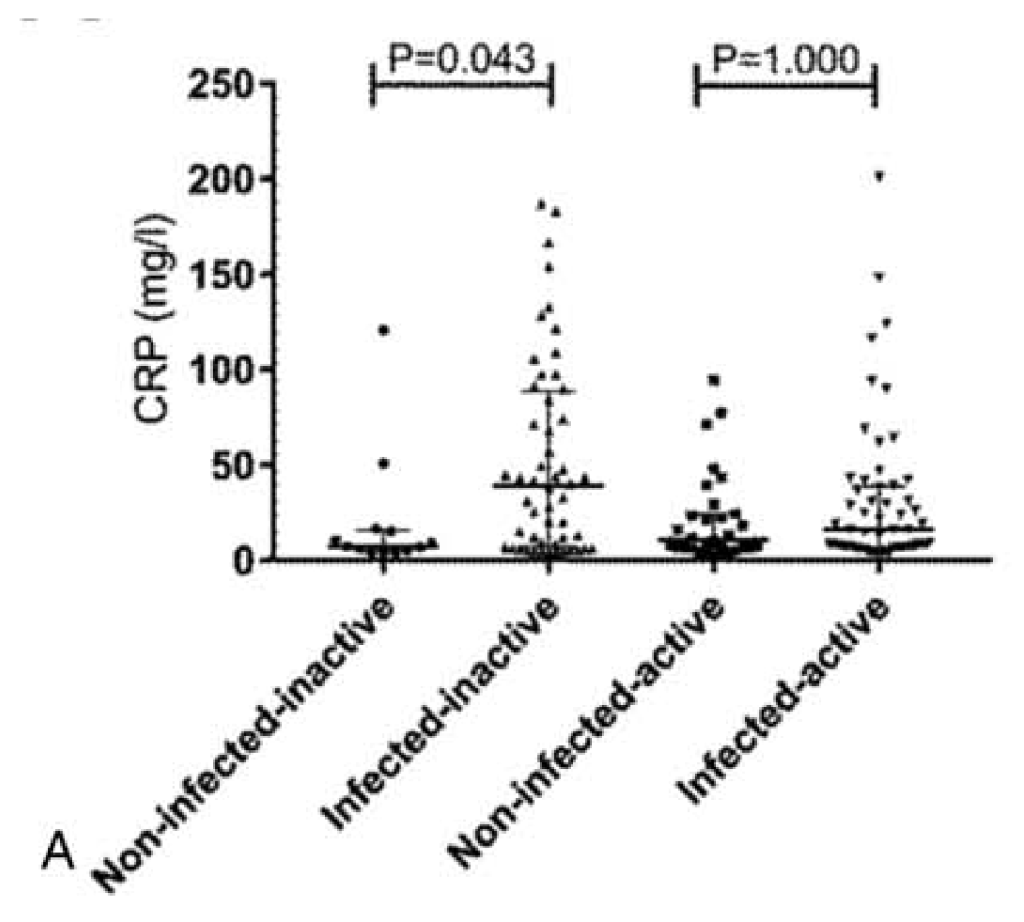

The earliest report alluding to this discordance was published in 1951 by Alan Hill. He wondered whether CRP could be used to track disease activity in various non-infectious inflammatory conditions, ranging from rheumatoid arthritis to dermatomyositis to lupus. For rheumatoid arthritis, the CRP was elevated in 56 of 84 cases, or about two-thirds. There were far fewer lupus cases. But of the four he did examine, none had an elevated CRP unless there was a concurrent infection. In 1979, a larger cohort found that CRP was elevated in 85% of patients with active RA and only 4% of patients with active lupus. In a more contemporary study, from 2019, a CRP of about 7 mg/L was found in inactive lupus and 12 mg/L in active lupus. But if you had active lupus with infection, the CRP rose to over 40 mg/L.

ESR, on the other hand, is typically elevated. And this difference has led some to suggest that the ESR-to-CRP ratio may help distinguish flares from infection: a high ESR-to-CRP ratio suggests a flare alone, while a lower ratio might suggest active infection as well. In the 2019 study, an ESR:CRP ratio of 15 or more was almost always active lupus alone, without concurrent infection.

To understand the discordance between ESR and CRP in active lupus, it helps to consider the immune response in various conditions. To do this, imagine a trigger, a receptor that senses it, and the characteristic cytokine signature it promotes upon activation. Ultimately, the cytokine signature determines whether CRP, ESR, or both are elevated.

A good example is gram-negative sepsis, a classic inflammatory state. Here, the trigger is often lipopolysaccharide, also known as endotoxin. This protein activates toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). TLR4 activation results in a robust cytokine profile characterized by tumor necrosis factor, IL-1, and IL-6. It’s the IL-6 that is mainly responsible for the marked increase in CRP production by the liver. And CRP is usually very high in gram-negative sepsis. In one study, the mean CRP was greater than 100 mg/L. Recall that in active lupus, the values were closer to 10 mg/L.

This same inflammatory cascade also leads to an increase in fibrinogen and immunoglobulins, which promote the aggregation of red blood cells and their sedimentation in a test tube.

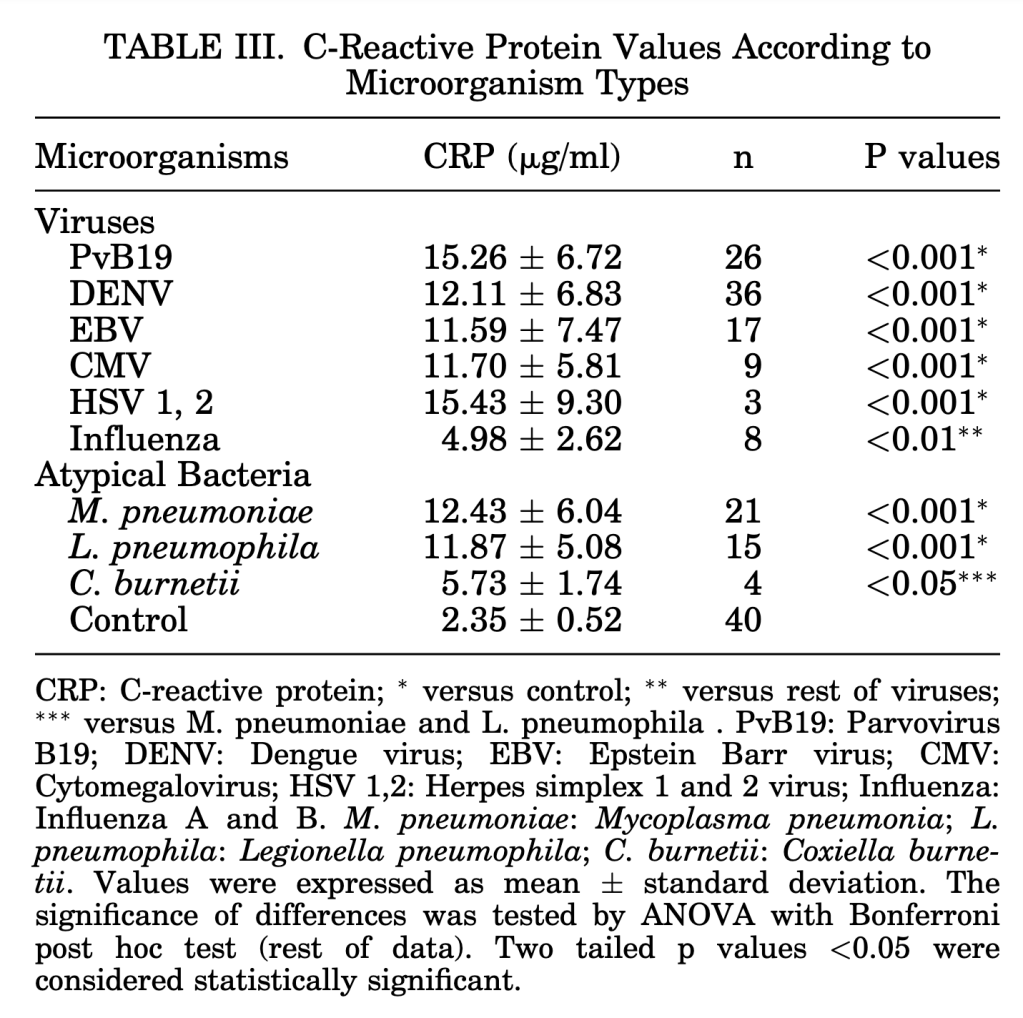

Epstein-Barr virus provides a good example of the immune response to a viral infection. Viruses consist of either DNA or RNA enclosed in a protein coat. So, unsurprisingly, the immune trigger in a viral infection is either DNA or RNA. EBV is a DNA virus, so DNA is a trigger. More specifically, unmethylated CpG-rich DNA. This type of DNA activates toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9). TLR9 activation results in a distinct cytokine profile, with a pronounced IFN-α response. Interferon was named for its ability to interfere with viral replication, so it makes sense that we see this sort of response during a viral infection.

Interferon, particularly type I interferons like IFN-α, suppresses CRP production. The primary mechanism involves interferon-α-induced shedding of membrane IL-6 receptors, leading to the release of soluble IL-6 receptors. This ultimately reduces the amount of IL-6 reaching the liver to stimulate CRP production. Additionally, type I interferons appear to have direct inhibitory effects on hepatic CRP synthesis, independent of IL-6 modulation. It should therefore be unsurprising that EBV is only associated with minimal elevations in CRP, consistent with an interferon-based immune response.

Some viral infections do have an IL-6 signature. COVID-19 is one example. We even use tocilizumab, a monoclonal antibody against IL-6, in some cases. In one of the largest randomized trials of tocilizumab in COVID-19, the median CRP was about 150 mg/L. But in these cases, the immune response isn’t just to the virus; it is also responding to the marked tissue damage and activation of TLR4, the same toll-like receptor we saw in gram-negative sepsis. This makes the cytokine profile resemble that seen in bacterial sepsis, at least in some cases. But COVID-19 also demonstrates how our attempts to put things into silos like “viral,” or “bacterial,” or “inflammatory” oversimplify. Still, we necessarily do this to understand the key features of diseases.

In lupus, the body is creating antibodies against nuclear components, including double-stranded DNA. It should come as little surprise that the immune cascade we observe is similar to that observed in a double-stranded DNA virus such as EBV. In lupus, the same TLR is activated as in EBV. And the immune cascade is nearly identical in lupus as in EBV. The trigger is dsDNA, which activates TLR9. TLR9 initiates a profound IFN-α response, as with EBV.

The interferon-based immune response is what dampens the CRP elevation we might otherwise see in the setting of immune activation. Unless a concomitant bacterial infection activates the IL-6 arm, the IFN arm predominates in active lupus, keeping the CPR normal or only modestly elevated. That’s one of the mechanisms that explain the high ESR but low CRP in active lupus. There are a few other mechanisms. For example, some patients have auto-antibodies directed against CRP. There are also genetic polymorphisms that may play a role.

The similarities between EBV and lupus are interesting because there may be a causal relationship between the two. First, EBV seropositivity in those with lupus is 100%, compared with approximately 92% in controls. Patients with lupus also have high rates of EBV reactivation. It could be that EBV leads to reprogramming of autoreactive B-cells to induce autoimmunity in those who are otherwise predisposed. Despite this, it’s too simplistic to say that EBV causes lupus, even if it is in the causal chain for some, or even all, patients. But lupus looks like what would happen if the immune system believed EBV was permanently present and could never be cleared.

Other conditions with an interferon gene signature are also associated with a high ESR but normal CRP. These include Inflammatory myopathies, primary Sjögren’s syndrome, and systemic sclerosis. The reverse is also seen: ERS is low and CRP is high. Thinking back to the patient with gram-negative sepsis, if they also have disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), they might have a markedly elevated CRP but a very low ESR. Fibrinogen, which typically cross-links red blood cells, leading to faster fall and a higher ESR, is low, resulting in less cross-linking and a normal or even low ESR.

Multiple myeloma often presents with a markedly elevated ESR and normal or minimally elevated CRP. Here, red blood cell aggregation isn’t due to fibrinogen but to immunoglobulins produced by plasma cells. That’s what causes the elevation in ESR. The high ESR has even been suggested as a marker for early detection of multiple myeloma.

Take Home Points

- Active lupus is characterized by an elevated ESR but a normal CRP, an example of ESR:CRP discordance.

- The low CRP is primarily driven by a predominantly interferon-mediated immune response in active lupus.

- The cascade observed in active lupus is very similar to that seen in EBV, a dsDNA virus linked to the pathogenesis of lupus.

Sponsor

This episode was sponsored by FIGS. FIGS is offering 15% off your first purchase. Just go to wearfigs.com and use the code FIGSRX at checkout

Listen to the episode!

https://directory.libsyn.com/episode/index/show/curiousclinicians/id/4008218

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Tony Breu

◾️Show notes written by Tony Breu and Giancarlo Buonomo

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Breu AC, Abrams HR, Cooper AZ, Buonomo G, Manna, M. When CPR Goes Missing. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. February 11, 2026.

Image Credit: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/C-reactive_protein