Why does cirrhosis cause high SAAG ascites?

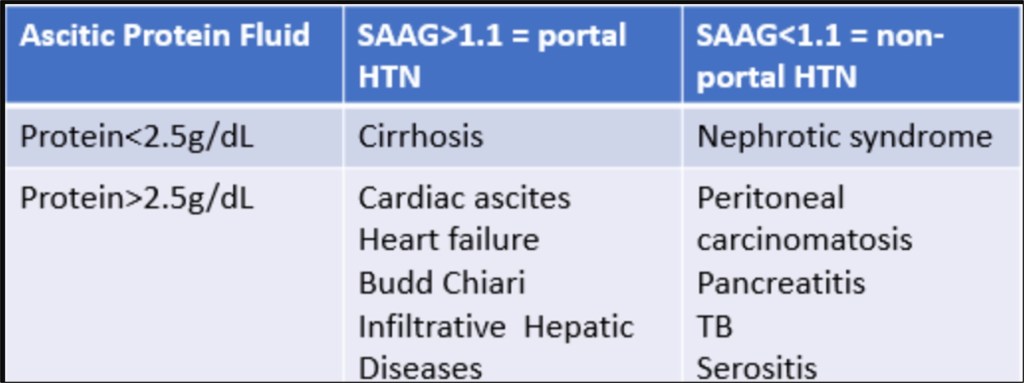

Other than when there’s Thai food at noon conference, it’s the best part of the day on inpatient medicine. A patient comes in with ascites, they get a diagnostic paracentesis, you look at the fluid albumin and subtract it from that serum albumin that you pray you remembered to order before the tap. This is the serum ascites-albumin gap (SAAG). You google that chart that you’ve somehow never remembered to bookmark, and, unlike most other lab values in medicine, it gives you a clear answer: If the SAAG is ≥ 1.1 g/dL, the ascites is due to portal hypertension, and your differential has just been narrowed to cirrhosis … and then cirrhosis … and then cirrhosis … and then finally some other causes like heart failure and various types of thrombosis.

SAAG is mercifully easy to calculate and use. But how many of us actually know why all of our patients with cirrhosis have a high SAAG? That’s why we’ve devoted a whole episode to understanding how this small number tells us an enormous amount about a patient’s pathophysiology.

To understand SAAG, we first need to understand ascites, and to understand ascites we have to understand capillaries. There are three basic types of capillaries in the body: Continuous, fenestrated and sinusoidal. Continuous capillaries have an uninterrupted endothelial lining joined by tight junctions and supported by a complete basement membrane, which makes them ideal for spaces like skin, lungs and the central nervous system where you don’t want too much leakage. Fenestrated capillaries, which have small pores (fenestrations), are in places like the glomeruli of the kidney where rapid, but controlled, filtration and absorption of molecules needs to happen. Sinusoidal capillaries have more of an “open-door policy.” Also known as discontinuous capillaries, they are large and have irregular lumens with wide gaps between endothelial cells and minimal basement membrane. This allows for much freer passage of large molecules like proteins. These capillaries exist primarily in the spleen, bone marrow and, pertinent to this episode, the liver.

“Hold on,” you may be thinking. “This makes no sense. High SAAG means that the ascites has less albumin. If the liver capillaries are leakier than a papier-mâché canoe, and portal hypertension is usually from liver disease, shouldn’t the fluid coming out of them be chock-full of albumin, making the SAAG low, not high?”

It’s a great question, and relates to the next one we need to answer: Where does portal-hypertensive ascites actually come from? Leading into the 1950’s, the thought was that ascites was simply due to a buildup of hydrostatic pressure in the portal system, and this pressure eventually backed up into the mesenteric vessels of the abdomen. Unlike the liver capillaries, mesenteric capillaries are continuous, and so the pressure would force out fluid but not much albumin.

It was a very logical conclusion, but not the whole picture. To be sure, excess pressure in the portal system can definitely cause ascites: Most cases of hepatic vein (Budd-Chiari syndrome) or inferior vena cava thrombosis produce ascites even in the absence of underlying liver disease. However, when just the portal vein is occluded (like in portal vein thrombosis), which should theoretically cause pressure buildup in those mesenteric vessels, we don’t often see large-volume ascites, and sometimes we see no ascites. Schistosomiasis (a parasitic infection and one of the leading causes of portal hypertension worldwide) can cause terrible portal vein fibrosis due to inflammation from egg deposition. Patients may have many classic signs of portal hypertension such as splenomegaly and varices, but rarely have significant ascites.

What’s going on here? Look closely at the diagram above and think about the diseases we just discussed. In Budd-Chiari syndrome and IVC thrombosis, the pressure backs up directly into the liver, whereas in portal vein thrombosis and schistosomiasis, the liver itself isn’t “feeling” the pressure. There are some old experiments where the liver was surgically moved to above the diaphragm and the IVC ligated to simulate portal hypertension. The resulting fluid accumulated in the chest, not the peritoneal cavity. Overall, this suggests that portal hypertensive ascites is coming from the liver, not the mesenteric vessels.

“Wait a second,” you’re probably saying. “This all literally proves my initial point. If the ascites if coming directly from the liver and the liver has all those leaky capillaries, shouldn’t the ascites in cirrhosis have just as much albumin as normal serum?”

Again, a very good question, and this leads us to our final area of exploration. Those leaky liver capillaries are organized in small beds called sinusoids, which connect the portal and central veins. In cirrhosis, a process called “capillarization” occurs. First described in 1963 by by Fenton Schaffner and Hans Popper, capillarization refers to a chronic inflammatory sequela in which hepatic stellate cells deposit extracellular matrix in the Space of Disse. This fibrosis impedes the exchange of proteins, including albumin. As cirrhosis progresses, capillarization worsens, and the hepatic sinusoids essentially turn into continuous capillaries.

Does this mean we can track the progress of cirrhosis using SAAG? Unfortunately, this is not a well-studied question. One 1968 study by Charles Witte and William Cole tracked the total protein content of ascites as cirrhosis worsened and found that as liver fibrosis increased, the ascitic protein went down. SAAG was not invented at this point, but as albumin is a protein, the total protein is a good enough proxy.

So, there’s the basic answer to our initial question: Cirrhosis causes both portal hypertension and capillarization of hepatic sinusoids, leading to leakage of low-albumin fluid. Of course, the ultimate answer may be more complicated. Remember those ultra-tight mesenteric vessels that we seemed to dismiss? Some researchers argue that while cirrhosis patients with relatively high ascitic protein content but still high SAAG (i.e., low ascitic albumin) probably have ascites purely coming from the liver, as disease progresses, splanchnic arterial vasodilation also does, which causes the mesenteric capillary hydrostatic pressure to rise enough to eventually force albumin-poor fluid out as well.

There are a million other questions to answer about ascites. For example, why do heart failure and IVC thrombosis also cause high SAAG if those diseases don’t necessarily causes hepatic fibrosis? And why do we use total ascitic protein to help us distinguish them from cirrhosis? Those are questions for another day. For now, we hope that this episode helps you the next time you pore over paracentesis results and wonder why that patient with jaundice, a swollen belly and a long history of alcohol use has a SAAG of ≥ 1.1 g/dL.

Take Home Points

- A non-cirrhotic liver contains the leakiest of all capillaries, known as sinusoidal capillaries.

- Despite this, the ascites of cirrhosis has a low albumin content.

- The main reason for this is capillarization of the sinusoidal capillaries, in which fibrosis restricts the movement of plasma proteins.

- As cirrhosis progresses, the continuous capillaries of the mesentery also contribute to high-SAAG ascites.

Sponsor

This episode was sponsored by FIGS. FIGS is offering 15% off your first purchase. Just go to wearfigs.com and use the code FIGSRX at checkout

Listen to the episode!

https://directory.libsyn.com/episode/index/id/39189005

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Tony Breu

◾️Show notes written by Tony Breu and Giancarlo Buonomo

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Breu AC, Abrams HR, Cooper AZ, Buonomo G, Manna, M. On Sinusoids and SAAGs. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. November 26th, 2025.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons