Why do lobsters age more slowly than we do?

We want to tell you a story about George … the lobster. George was caught off the coast of Newfoundland in 2009, weighing a whopping 20lbs (for comparison, most of the lobsters you’d eat in a restaurant weight between 1-5lbs). He ended up in the tank of a seafood restaurant in New York City, where a patron noticed his size and called PETA. They estimated, based on his size, that George was 140 years old and successfully petitioned the restaurant to send him back to a retirement community for lobsters (the coast off of ritzy Kennebunkport, Maine). As Maine fishermen are forbidden by law to catch lobsters above a certain weight, George may still be happily scuttling across the ocean floor in his 15th decade.

At this point, you may be wondering why the Curious Clinicians is sharing this heartwarming shellfish story with you. George is a great example of how lobsters age differently than humans. Not only can they live longer (although average lifespan is ~50 years), but they keep growing as they get older. Why does this happen?

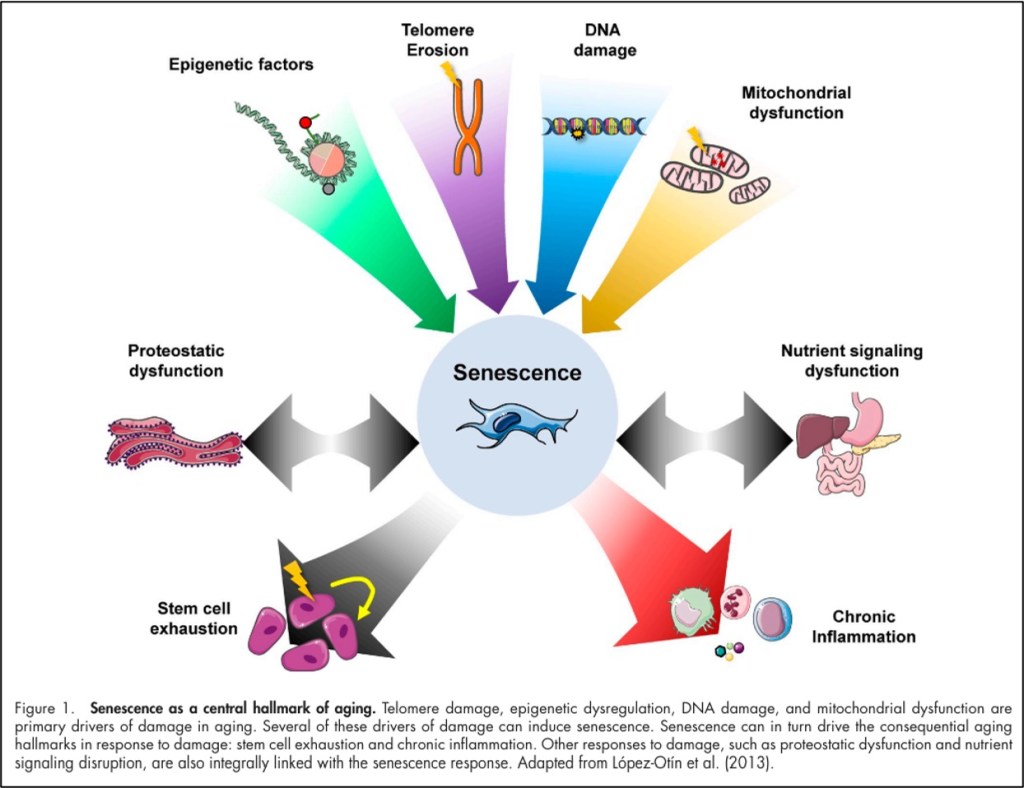

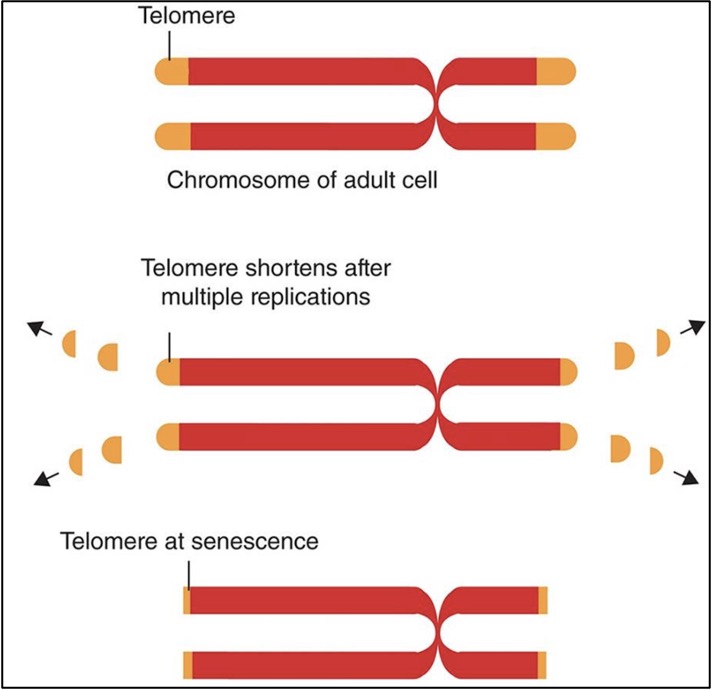

For most humans, aging looks something like this: We stop growing at the end of puberty, gradually lose our fertility (with obvious differences between males and females), and then experience increasing physical and cognitive decline in our last years. Aging is driven by senescence, or the aging of individual cells. Over time, cells accrue DNA and mitochondrial damage, as well as erosion of their telomeres, the repeating nucleotide sequences that cap DNA strands and prevent them from shortening during replication. Telomerase, an enzyme which can replete the telomere, is active in reproductive cells but not in other adult somatic cells. As a result, the telomere slowly loses its nucleotides (~80 base pairs a year before the age of 40, and ~40 a year from then on). Once telomeres reach a critically short length, the cell enters senescence.

Senescence is defined by impaired cellular function, chronic inflammation and stem cell exhaustion. Senescence can be beneficial in contexts like wound healing, as old tissue is cleared to make way for new. All cells eventually deteriorate though, making us more prone to things like dementia, cancer, infection and eventually organ failure and death. It’s no surprise, therefore, that there’s great interest in developing medications to delay senescence, and in theory, delay aging. These drugs, known as senolytics, include everything from vaccines against senescence markers on cell to producing T cell chimeras that target senescent cells to antibodies against β2-microglobulin (a senescent cell marker).

Lobsters, it seems, do not experience senescence. Researchers in Germany tested every organ (including the marvelous hepato-pancreas) in lobsters and found they have high telomerase levels. Granted, these lobsters were juveniles, but if we assume that these high telomerase levels don’t wane, that could explain how lobsters keep growing and reproducing long after a human would have.

That extra telomerase seems to work in lobsters’ favor. But, we have to consider how turning on telomerase is also a way that cancer cells endlessly divide. Are lobsters at a higher risk of cancer? It’s actually the opposite – very few lobsters are known to have had cancer. Sequencing of the American lobster genome has revealed 3 copies of the TP53 gene, which encodes for the powerful tumor-suppress p53 protein. Although not nearly as many as elephants, those extra copies of TP53 may provide increased cancer protection. However, as UMass-Boston marine biologist Dr. Michael Tlusty told us, we should be cautious about this “lobsters don’t get cancer” theory, as it’s extremely difficult to estimate how high cancer rates really are, as tumors could be hidden under shells, and moreover, have you ever heard of a lobster autopsy?

If lobsters don’t really “age” and don’t get cancer, then what do they die of? Other than finishing up in the belly of a fish, or in a hot dog bun with mayo, lobsters can, in a sense, die of “natural causes.” As they grow in size, they have to keep molting their exoskeletons, which eventually grows so metabolically demanding that they can’t maintain them.

Lobsters certainly age slower (and better) than humans. But some of their oceanic neighbors have them beat. Greenland sharks can live 270-plus years, quahog clams over 500, and the deep-ocean glass sponge an astonishing 10,000 years. However, Turritopsis dohrnii and Hydra are the two species that may actually be biologically immortal. The former is a tiny jellyfish which can reverse its lifecycle if injured, such that it can endlessly rejuvenate. The latter is a freshwater invertebrate which is made mostly of stem cells, which gives them a senescence-free “fountain of youth” to draw from.

Finally, check out rum from Rosalie Bay, the worlds first ocean conservation rum distillery! The rum, produced from sugar grown on the island of Dominica and aged in casks previously used for bourbon, is made by our host Avi Cooper’s step-brother Jacob. All the profits go to local ocean conservation efforts, one of the reasons they were recently featured on the Rumcast podcast. The rum can be bought direct in Boston, or shipped elsewhere online, so So check them out and support this important conservation work and the sugar cane farming community in Dominica!

Take Home Points

- Lobsters live longer than you might expect and don’t appear to undergo senescence

- This is confounded by the inexact nature of lobster age estimation

- Somatic cell telomerase activation in lobsters may play a role in avoiding senescence, and in concert with that, they also have extra TP53 gene copies, which may protect against cancer

- There several marine species that live much longer than lobsters, though, including glass sponges which can live for over 10,000 years

- Turritopsis dohrnii and Hydra species are the only known to have the potential for biological immortality

Listen to the episode!

https://directory.libsyn.com/episode/index/id/34612580

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Sponsor

Freed is an AI scribe that listens, transcribes, and writes medical documentation for you. Freed is a solution that could help alleviate the daily burden of overworked clinicians everywhere. It turns clinicians’ patient conversations into accurate documentation – instantly. There’s no training time, no onboarding, and no extra mental burden. All the magic happens in just a few clicks, so clinicians can spend less energy on charting and more time on doing what they do best. Learn more about the AI scribe that clinicians love most today! Use code: CURIOUS50 to get $50 off your first month of Freed!

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Avi Cooper

◾️Show notes written by Giancarlo Buonomo and Avi Cooper

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Cooper AZ, Abrams HR, Breu AC, Buonomo G. Long Lives the Lobster. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. December 25th, 2024.

Image Credit: Shutterstock

Fascinating! Keep up the great work!

LikeLike