Why do we make antibodies to ABO blood groups even without exposure?

There’s a reason many patients admitted to the hospital get a Type and Screen (T&S) to determine their ABO blood group. If that patient needed a transfusion and got an incompatible blood type, they could become severely ill or even die from an acute hemolytic transfusion reaction (AHTR), in which the immune system reacts violently to antigens (usually A or B) on the transfused red blood cells.

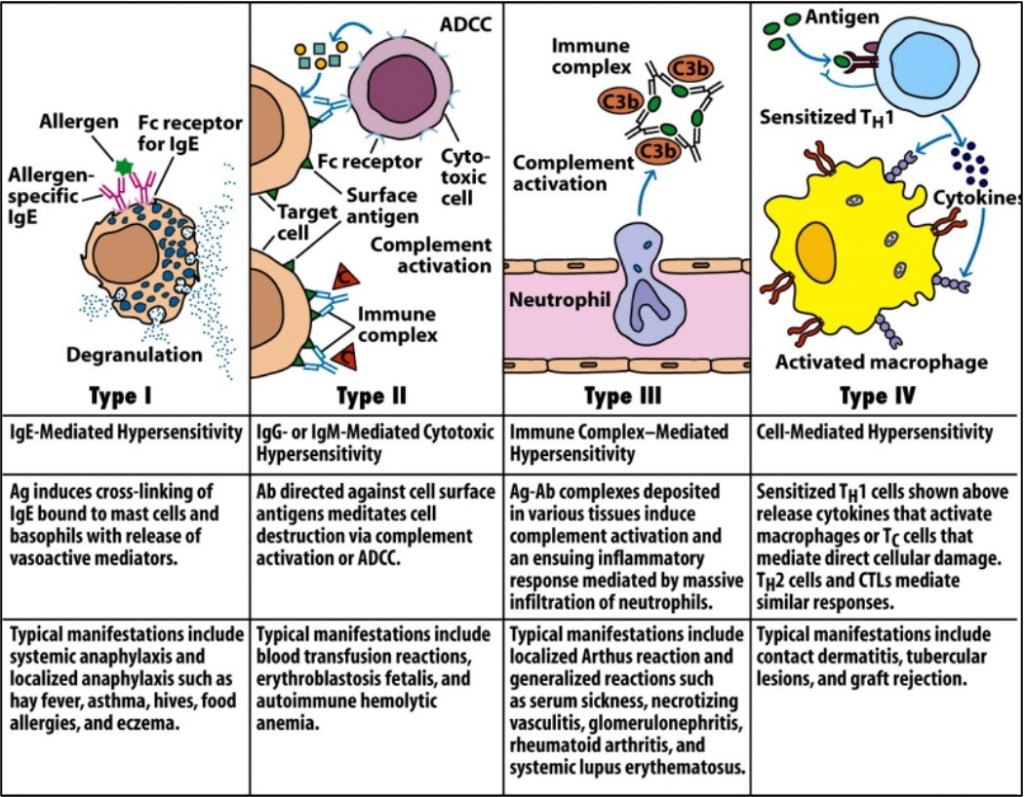

In addition to being scary for provider and patient alike, the AHTR is also a bit perplexing. The body has two basic types of immune defenses: “Innate,” which requires no prior exposure to an antigen and is a first-line defense against obviously “foreign” pathogens like bacteria or parasites, and “adaptive,” which is antibody-mediated and develops after exposure. As a reaction that can occur without any prior exposure (i.e, prior transfusions), AHTR has some similarities to innate reactions. But innate reactions are typically formed against non-human, non-self antigens, not antigens that are on the majority of humans’ blood cells. So why would someone already have antibodies against seemingly-harmless antigens that they’ve never been exposed to?

To answer this question, we should first discuss transfusion itself. Since William Harvey first showed how blood circulates in 1628, people have been trying to transfuse. The first successful animal-to-human transfusions occurred in 1667, but physicians soon realized that most patients had bad reactions to animal blood. In fact, the first successful human-human transfusion wasn’t until 1818, when Dr. James Blundell transfused approximately 4 ounces of blood from a husband to his wife who was dying of postpartum hemorrhage.

Although some human-human transfusions were successful in the following years, the problem of severe reactions to transfused blood continued to frustrate until the turn of the century. Karl Landsteiner, an Austrian physician, noted that the blood of one person would often agglutinate when exposed to the blood of another person. He hypothesized that this was due to an inherited difference in each persons blood, and that this agglutination was a mini-version of the adverse reactions seen in transfusions. He theorized that there were 3 different blood groups: A, B and C. Although Landsteiner’s classification would later be modified (C became O, and AB was added), it was enough in 1907 for Ludvig Hektoen to propose using these groups to “cross match” donor and recipient blood: If they were mixed and didn’t agglutinate, they were compatible.

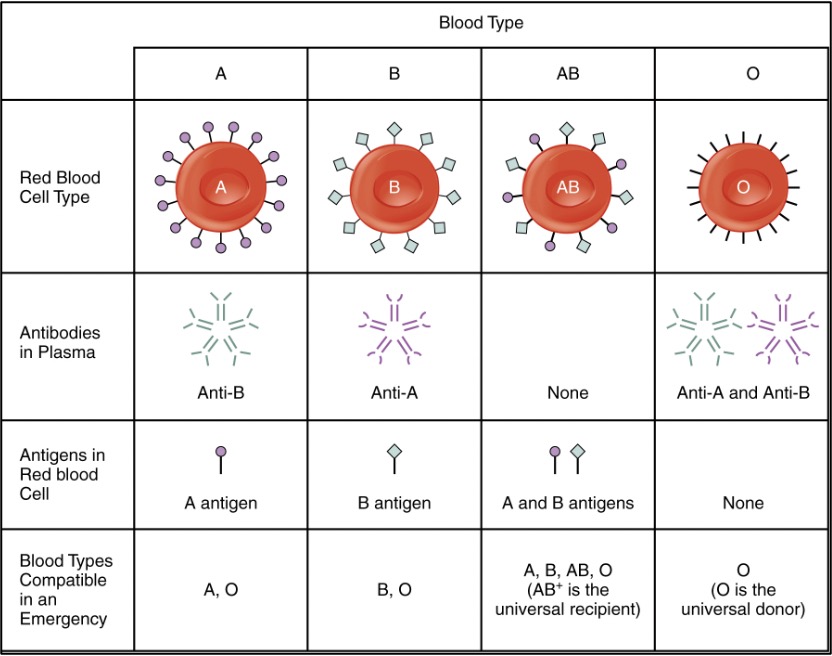

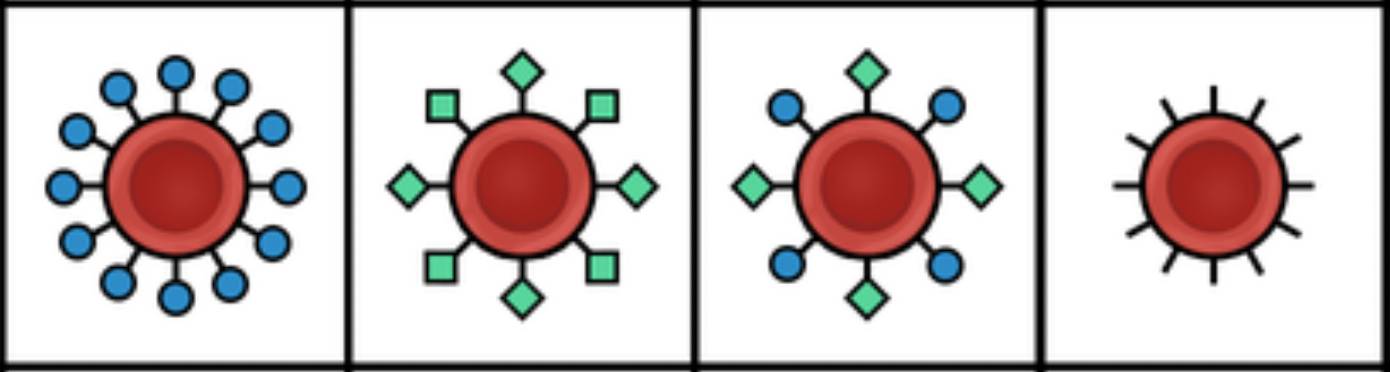

Landsteiner and Hektoen’s work paved the way for both safe human-human transfusions and the elucidation of many different blood groups. Although ABO is still the most clinically important, the list of others is immense: Rh, MNS, P, Kidd, Kell, Lewis, Lutheran, Duffy, I, H, and many more. Each group refers to a molecule on the surface of the red blood cell (RBC): A and B antigens are carbohydrates, while the Rhesus “D” antigen in the Rh group is a transmembrane protein. Blood type names would be very long if every antigen was included, so we usually just mention A, B, O (meaning neither A or B is present) and Rh (which accounts for the +/-).

To put it simply, the antigens are your red cells determine who you can give blood to and the antibodies you have determine who you can get blood from. For example, AB+ blood has both RBC surface antigens, so it can only be given to fellow AB+ people, but since it won’t have any anti- A, B or Rh antibodies, people with an AB+ blood type can receive blood from any other ABO type. On the flip side, people with O- blood type have none of the 3 antigens (A, B, and Rh) and can be given to (almost) everyone, but will have antibodies to A, B and Rh and so can only receive from a person who also has O- blood type.

Sort of. The important caveat is that while anti-Rh antibodies can cause hemolytic reactions, you only develop them if you’ve been exposed to Rh. Since anti-Rh can have developed during pregnancy (such as an Rh- mother carrying an Rh+ child and absorbing some of its blood) or prior transfusions, current practice is to be safe and not transfuse a Rh- person of childbearing potential if there is time to wait for a compatible Rh- unit. This brings us back to our initial question, though. Even without any prior exposures, humans begin developing primarily IgM antibodies to the A and B antigens they don’t have starting at 3-6 months of age (with around 18% even having them as young as 1 week), reaching a peak at 5-10 years old. In other words, no exposure to other blood types is necessary. Why does this happen? And why does it happen with the ABO blood group, but not the other blood groups?

It turns out that exposures do happen early in life, just not to blood. For decades, researchers have noticed that certain foods are associated with hemagglutinin production – for example, some legumes can cause production of antibodies similar to anti-A ones. Even mice who are raised in perfectly sterile conditions still produce anti-ABO antibodies, which the researchers theorized could be due to their diet.

More important, however, is that many pathogens have antigens that are similar to our own A and B. Early experiments in animals, for example, showed that infections with bacteria like shigella and pneumococcus generate ABO-type-specific antibodies. Over thousands of years, our bodies evolved to produce those antibodies as a preemptive defense before we’d even been infected. However, as those bacterial surface polysaccharides are homologous to A and B, the antibodies we produce can attack RBCs that have the wrong antigens. Since many animals have similar surface carbohydrates, xenotransfusion is also at high risk for a hemolytic reaction. The benefit of making these antibodies and getting some potential extra protection from pneumococcus has been present for many thousands of years.

Other blood groups may have antigens similar to other but less common infectious agents, like those responsible for leishmaniasis, trypanosomiasis, and mumps, which could explain why weak (IgM) antibodies are also often common to spontaneously occur, but it’s possible that since these infectious agents are less prevalent than pneumococcus and shigella, they might not exert the same evolutionary pressure to cause the strong antibody response in nearly all humans.

This episode draws upon a mechanism that we’ve explored in other Curious Clinician episodes, such as how Group A Strep infection leads to rheumatic fever, or why tick bites cause some people to develop a red meat allergy. In these cases, the body produces antibodies to ward off pathogens, but those antibodies then end up with unintended, similar-appearing targets. Anti-ABO antibodies are particularly challenging because, despite interfering with the relatively-new practice of blood transfusions, long-term evolution selected for their production starting at a young age. But they can be worked around: If a child needs a heart transplant and is under a year old, an ABO-incompatible heart can be tolerated!

Take Home Points

- Humans develop anti-ABO antibodies, primarily IgM, very early in life, without requiring prior exposure to these antigens

- We do this because of similarities between the ABO carbohydrates and antigens on bacteria, parasites, and in our food.

- This is distinct from many other antibodies we form to non-self blood groups, which require prior exposure and primarily form IgG antibodies.

Listen to the episode!

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Sponsor

Freed is an AI scribe that listens, transcribes, and writes medical documentation for you. Freed is a solution that could help alleviate the daily burden of overworked clinicians everywhere. It turns clinicians’ patient conversations into accurate documentation – instantly. There’s no training time, no onboarding, and no extra mental burden. All the magic happens in just a few clicks, so clinicians can spend less energy on charting and more time on doing what they do best. Learn more about the AI scribe that clinicians love most today! Use code: CURIOUS50 to get $50 off your first month of Freed!

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Hannah Abrams

◾️Show notes written by Giancarlo Buonomo and Hannah Abrams

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Abrams HR, Breu AC, Cooper AZ, Buonomo G. Automatic ABO. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. December 11th, 2024.

Image Credit: Labster

this is a terrific topic–an important biologic idea hiding in plain sight. Beauty. In transplant, rejection doesn’t occur immediately (hyperacute), I think, unless it is by this mechanism or if there is pre-sensitization, which is the exact point made about ABO being an automatic antigen.

LikeLike