How does a bacterial species called Deinococcus radiodurans withstand extreme levels of radiation?

What comes to mind when we say tiny but mighty? Well, if Deinococcus radiodurans didn’t cross your mind, maybe it will earn your respect after this segment, so much so that it may come to mind the next time someone asks you that question. In our previous episode, “Wherefore Iodine?”, we learned about why iodine administration was a key public health intervention in Eastern Europe following the Chernobyl disaster. Then, in a follow-up episode, “The Mold that Eats Radiation for Breakfast”, we covered how various species of black radiation-eating fungi are not only surviving, but thriving within and around Chernobyl. In that episode, we discussed the concept of radioresistance, which refers to the degree to which an organism can withstand various levels of radiation exposure. And that brings us to this segment: how does the most radioresistant organism on the planet, a tiny bacterium called D. radiodurans, withstand extreme levels of radiation?

D. radiodurans is an extremophile, a term used to describe an organism that can live and even thrive in the most extreme environments. And as mentioned in a previous episode, bacteria are the most tolerant of environmental extremes among any form of life. The term “extremophile” was coined in 1974 by R.D. MacElroy, a scientist at NASA, when he described the microbes that exist in harsh environments that most forms of life cannot tolerate, such as extremes of temperature, pH, pressure, or radiation exposure. Fascinatingly, Koki Horikoshi and Alan Bull, in their book Extremophiles Handbook, note “definitions of extreme and extremophile are of course anthropocentric; from the point of view of the organism per se, its environment is that to which it is adapted and thence is completely normal.” In other words, what we humans view as extreme is entirely normal to an extremophile bacterium like D. radiodurans.

D. radiodurans is just remarkably resilient to radiation damage. Just to put it into perspective, according to the CDC, humans have an LD50/60 (dose at which ~50% die within 60 days after an entire body high dose penetrating radiation) of about 2.5–5 Gy, whereas D. radiodurans can survive 5,000–15,000 Gy of acute ionizing radiation with no loss of viability. Apparently, it has been nicknamed “Conan the Bacterium” due to its ability to survive such extreme conditions. It was discovered in 1956 when it was isolated from cans of meat that had gone through sterilization using high-dose radiation bursts.

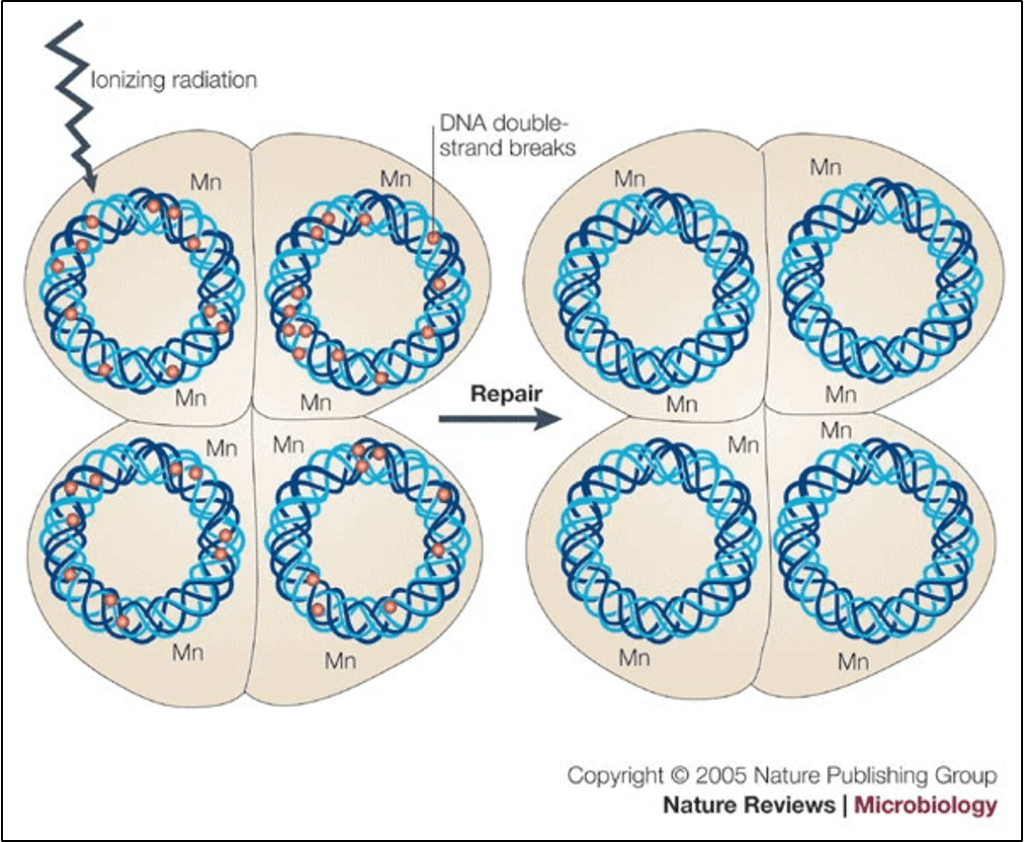

So, how does D. radiodurans survive these conditions? To answer this, we will draw from a 2005 review in Nature, titled “Deinococcus radiodurans – The Consummate Survivor,” by Michael Cox and John Battista. In a very general sense, this bacterium’s superpower involves resistance to DNA damage. Radiation damages DNA by causing a double-stranded break where that double helix strand of DNA fully ruptures. Like other bacteria, D. radiodurans employs double-stranded DNA repair mechanisms, where a homologous region on another intact segment of DNA serves as a template for repair. However, D. radiodurans also possesses different forms of certain DNA repair enzymes, which enable more efficient and accurate repair compared to other bacteria.

Additionally, D. radiodurans has redundancy built into its genome, comprising approximately 3,000 individual genes. It accomplishes this by having at least four copies of its genome, so even if a DNA break damages one copy of a gene, it still has at least three other copies of that gene. These extra copies also make D. radiodurans better able to repair DNA strand breaks when they arise, because they can be used as a template to patch the rupture. However, Cox and Battista point out that this mechanism is more speculative because other bacteria, which are not equally radioresistant to D. radiodurans, can also increase their gene copies during phases of active cellular division. Nonetheless, it does make sense that having more gene copies in general would help an organism better absorb damage from ionizing radiation.

Furthermore, D. radiodurans organizes its DNA into a circular ring, which is a fairly standard arrangement for bacteria. However, it also has a more condensed genome, which some molecular biologists have theorized might help keep breaks closer together rather than separating within the cell, making its DNA more radioresistant. Finally, D. radiodurans also has more manganese in its DNA than other types of bacteria. Since it is a positively charged cation, it may act as a protective agent by serving as a reactive oxygen scavenger or by facilitating further condensation of the DNA.

Radiation doesn’t only damage DNA though, it also oxidizes proteins hindering their function. A 2010 paper by Anita Krisko and Miroslav Radman, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, found that D. radiodurans is exceptionally adept at preventing radiation-induced protein oxidation through an unknown mechanism, but they presumed the involvement of a cytosolic antioxidant compound.

Is there any advantage to this type of extreme radioresistance? We discussed in “The Mold that Eats Radiation for Breakfast” that some of these microbial radioresilience features might relate to the environment that life had to contend with on the early Earth, where radiation levels were higher. However, Cox and Battista theorized that the primary reason might be that having hardier, sturdier, and easier-to-repair DNA is itself beneficial, regardless of whether radiation, changes in pH, temperature, or desiccation damage that DNA. They drew a connection in particular with desiccation, arguing that the evolutionary pressure to be able to survive DNA damage from drying out for a bacteria is really strong, and it may be that the ability to tolerate extremely high doses of ionizing radiation may simply be a byproduct of resistance to desiccation. Resilient DNA is the underlying theme there, and presumably proteins as well. This is an example of exaptation, where a feature evolves for a particular reason but then gets used to serve a different purpose altogether. In “The Mold that Eats Radiation for Breakfast,” we also discussed how NASA is exploring the use of radioresistant fungi as potential radiation shields for a future human mission to Mars. These non-human forms of life are often far more resilient than we are at withstanding environmental and physiological extremes.

But this also begs the question, if D. radiodurans is that hardy, do we have to worry about it or other extremophiles potentially colonizing other planets? This is the inverse of the so-called panspermia hypothesis, which posits that the essential ingredients for life on Earth arrived on our planet from a meteor impact. The term for this concern is interplanetary contamination, and it is a real concern. In 2001, an article titled “Infecting Other Worlds” was published in the magazine American Scientist by Richard Greenberg, where he noted that the Apollo 12 mission, which was of course the first to land on the moon, retrieved probes that had been sent to the moon years earlier. Upon returning to Earth, live bacteria were found to be living inside the machinery, despite the machinery having been on the moon’s surface. As we continue to explore the Solar System, Greenberg frames this as an ethical quandary that we must grapple with as a scientific community and as a species.

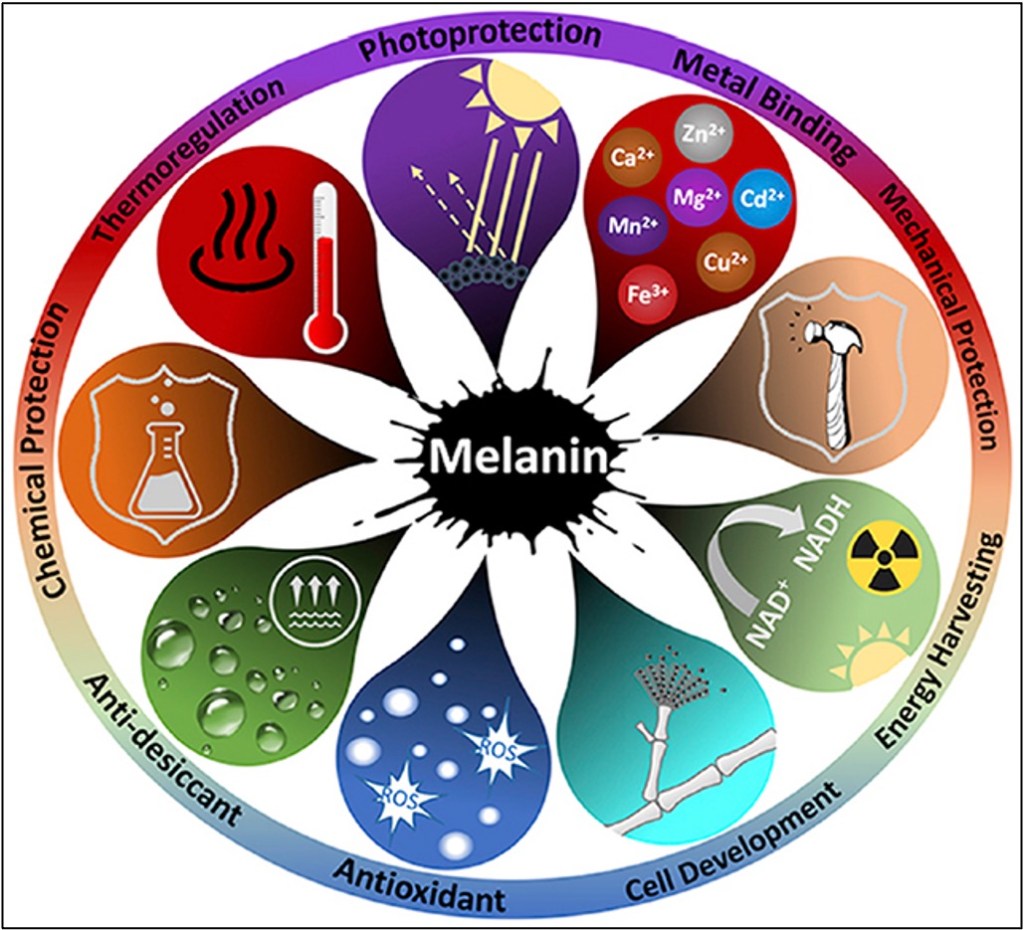

As cool as this tiny bacteria is, the melanin in fungi also serves a similar purpose, where extreme radioresistance might be an epiphenomenon related to being able to protect DNA from any source, including desiccation. This paper from the fungal world suggests that melanin in fungal cell walls serves a function beyond simply protecting against radiation. Having melanin in a fungus’ cell wall just makes it sturdier in general, including being more resistant to things like desiccation, heat, and physical damage to cell walls. It protects fungi against the human immune system, thus making melanized fungi more pathogenic.

Take Home Points

- Deinococcus radiodurans is an example of an extremophile, and is perhaps the most resilient organism on the planet

- Mechanisms for its radioresilience involve genome construction, efficient DNA repair, and resistance to radiation-induced protein oxidative damage

- This capacity for radioresistance may be a byproduct of resistance to DNA damage from desiccation

- Melanin in fungi increases their virulence and pathogenicity via resistance from immune-mediated destruction

Sponsor

This episode was sponsored by FIGS. FIGS is offering 15% off your first purchase. Just go to wearfigs.com and use the code FIGSRX at checkout

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Avi Cooper

◾️Show notes written by Avi Cooper and Millennium Manna

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Cooper AZ, Abrams HR, Breu AC, Buonomo G, Manna, M. Extremophiles. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. November 12th, 2025.

Image Credit: Pixabay