What’s with the black mold growing inside Chernobyl?

In a recent Curious Clinicians episode about the tragedy of Chernobyl and the public-health effort to distribute iodine pills to the victims, we mentioned that the reactor that exploded (and even some of the wider fallout area) is now host to a curious organism: A black fungus that apparently eats radiation. How does radiation, which usually kills living things, end up sustaining something?

Much of this episode is derived from a fabulous article entitled “Ionizing Radiation: How Fungi Cope, Adapt, and Exploit with the Help of Melanin” by Ekaterina Dadachova and Arturo Casadevall, published in Current Opinion in Microbiology in December 2008. This story begins back in the years immediately following the Chernobyl accident, when it was noticed that there were plentiful amounts of black-colored fungi both proliferating around reactor #4 and even outside the reactor within the so-called exclusion zone, which is the 30 km of restricted area around Chernobyl because of radiation contamination. This isn’t a one-off mutant: Over 200 species of fungi have been isolated from the reactor and the highly-radioactive Red Forest, including Cladosporium cladosporioides, Penicillium lanosum, Penicillium roseopurpureum, Paecilomyces lilacinus and even cryptococcus neoformans.

It appears that these fungi aren’t just surviving the radiation, they’re thriving in it. The technical term is “radiotropism,” meaning the fungi grow towards the most radioactive areas. Even more amazing is that these fungi seem dependent on radiation to grow, a process called “radiostimulation.” The researchers we mentioned above took fungal samples from Chernobyl and found that they accelerated spore production when exposed to radioactive isotopes. Control fungi taken from areas that were uncontaminated did not start to make more spores after exposure to radiation. This suggested that the Chernobyl fungi had effectively undergone rapid evolution to not just tolerate but benefit from the radioactive environment in which they existed.

How is this possible? Aren’t Twinkies supposed to be the only thing that survives radiation? Well, let’s go back to the title of the article we cited: It had the word melanin in it. And what has radiation in it? Sunlight. Do you see where we’re going with this?

This is all speculative, but the idea is that the fungi are black because they have evolved to produce tremendous amounts of melanin, the same compound that causes humans to tan when exposed to the ultraviolet radiation of the sun. Melanin is effective at absorbing radiation, and the fungi are protected from DNA damage in their highly radioactive environment.

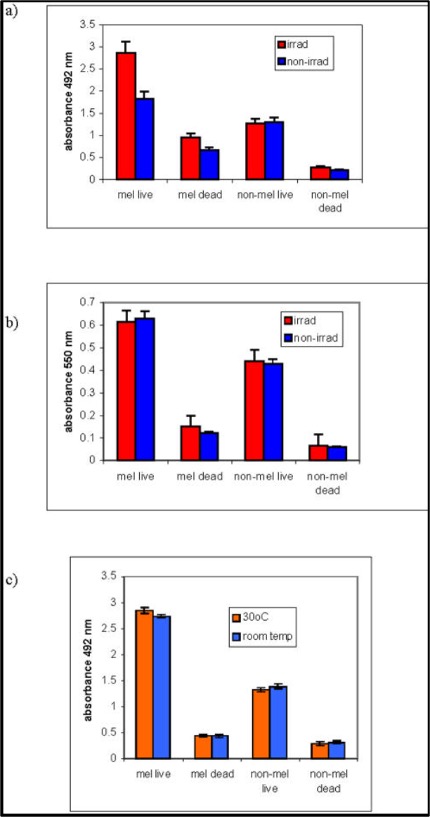

That explains how the fungi survive in Chernobyl, but not how they thrive. Why are they actively growing towards radiation? Again, this is all theoretical, but some scientists believe that the fungi perform “radiosynthesis” in the way that plants do photosynthesis. Plants use chlorophyll to absorb the radiation from sunlight and turn it into energy to power ATP production. Fungi may use melanin in the same way. One experiment showed that melanized fungi exposed to radiation showed enhanced growth compared to both melanized fungi not exposed to radiation and fungi that did not have melanin. When they looked metabolically at the fungi, the researchers found that the radiation changed the spin of the electrons on melanin, and it had 4 times as much capacity to donate an electron or reduce NADH when compared with melanin that hadn’t been exposed to radiation.

So, it seems that the Chernobyl fungi are indeed some of the hardiest beings on earth (even more so than cockroaches!). However, they aren’t even the toughest organisms when it comes to radiation. Remember Pinky, that Manatee-like creature from “The Magic School Bus”? He was a Tardigrade, a microscopic animal that can withstand up to 4,000 grays of radiation (the Chernobyl fungi can tolerate up to 1,000 grays). And even they aren’t the true champions – Deinococcus radiodurans, a bacteria, can withstand 15,000 grays!

It’s hard to imagine any organic material from the Chernobyl fallout being useful to humanity (in fact, a shipment of edible mushrooms from Belarus had to be recalled in France several years ago because they were still radioactive). But given how effective the Chernobyl fungi are at absorbing radiation, NASA has started experimenting to see if they could be cultivated on a mission to Mars as a potent shield for spacecraft on the harsh red planet.

Take Home Points

- Various species of black radiation-eating fungi are growing in and around the Chernobyl site

- The mechanism of this radiostimulation may be energized electron transfer by melanin

- This might have relevance for a future mission to Mars

- But the most radio-resilient being in existence, the bacteria Deinococcus radiodurans, stands alone

Sponsor

This episode was sponsored by FIGS. FIGS is offering 15% off your first purchase. Just go to wearfigs.com and use the code FIGSRX at checkout

Listen to the episode!

https://sites.libsyn.com/270773/114-the-mold-that-eats-radiation-for-breakfast

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Avi Cooper

◾️Show notes written by Avi Cooper and Giancarlo Buonomo

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Cooper AZ, Abrams HR, Breu AC, Buonomo G, Manna, M. The Mold that Eats Radiation for Breakfast. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. September 3rd, 2025.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons