Why does calcium deposit in blood vessels?

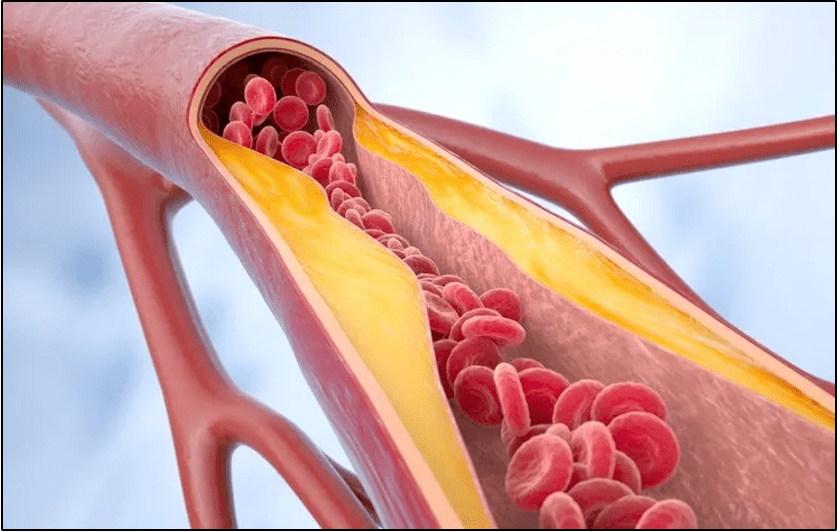

Ever heard of bone forming inside blood vessels? Even if you haven’t heard it expressed in those exact words, you most likely have come across the concept of vascular calcification. And in certain instances, fully formed bone is precisely the endpoint of calcium deposition in vessels.

The earliest recording of this discovery was made in 1863 by the German physician/scientist Rudolf Virchow, who described his observations within the blood vessel as “an ossification, not a mere calcification.” Then, in 1904, the pathologist CH Bunting was stunned to discover bone in the aorta of a man who died preoperatively of an infection. He noted that “at the base of this atheromatous nodule and lying directly adjacent to the calcified media are two masses of true bone…a capillary vessel surrounded by a layer of cells resembling osteoblasts closely applied to the wall of bone, the whole appearing to represent a Haversian canal.” He hypothesized that there was a metaplasia of connective tissue cells into osteoblasts.

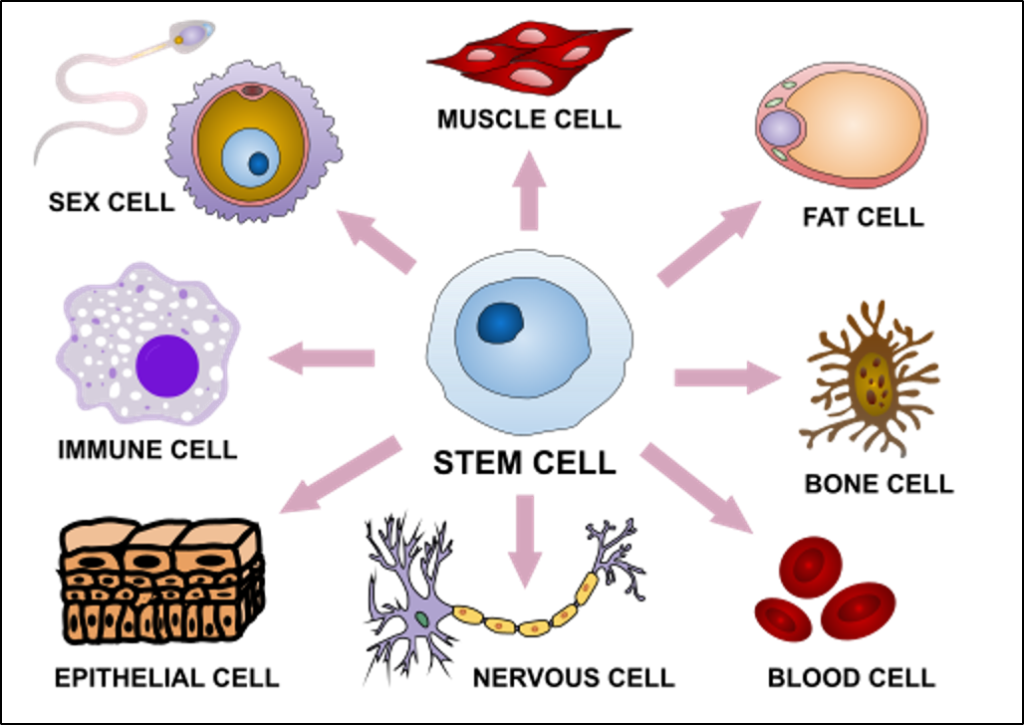

As both scientists observed many years ago, it turns out that smooth muscle cells in blood vessel walls can indeed undergo osteogenic transformation to take on roles similar to those of osteoblasts, the cells responsible for forming new bone. Although these cells are differentiated, they can undergo a process called transdifferentiation – the direct switch from one differentiated state to another without reversing to a pluriotent state.

The primary cause of vascular calcification is chronic inflammation. Oxidative stress causes vascular smooth muscle cells to start expressing osteogenic markers, while dying cells also begin to act as a nidus for calcium phosphate deposition, thereby initiating microcalcifications. This calcification is then followed by bone formation around the inflamed atherosclerotic lesion.

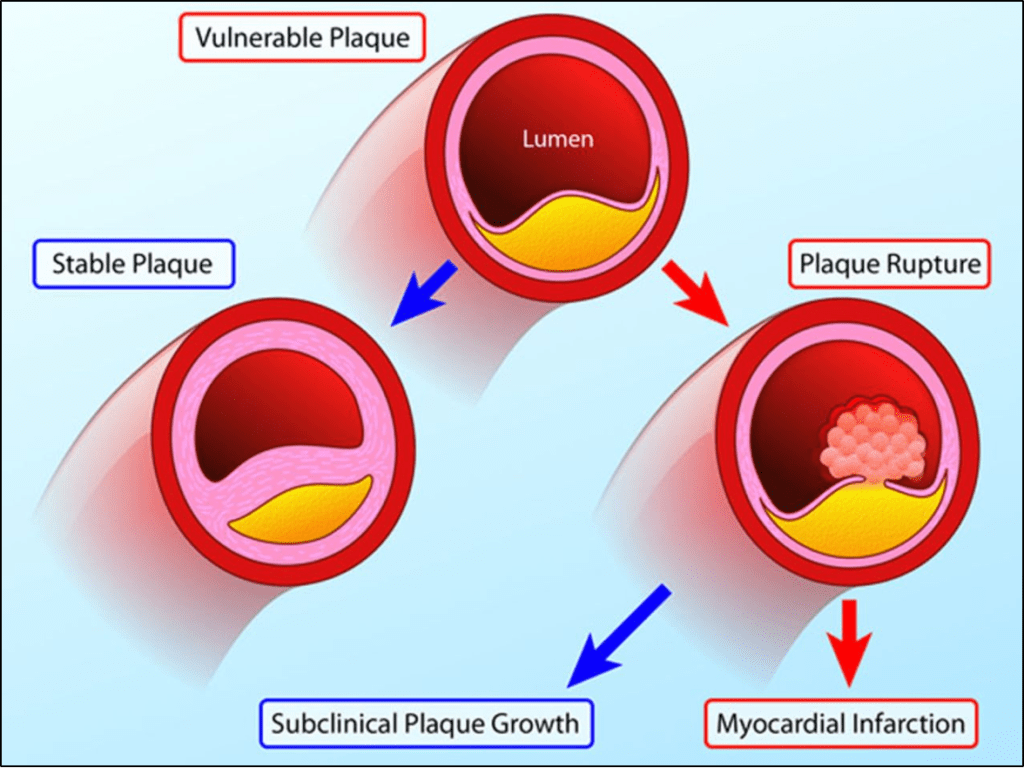

You might be wondering about the reason behind this, given that the elasticity and flexibility of blood vessel walls are crucial for blood vessel compliance. It has to do with the fact that calcification strengthens blood vessels that are under heightened stress. This is thought to be done in a biphasic process – microcalcification and macrocalcification.

Microcalcifications are typically less than 50 μm in diameter, and they are often located within the fibrous cap or necrotic core of atherosclerotic plaques. They are associated with inflammation and unstable lesions, and histopathological studies of coronary and carotid arteries show that microcalcifications are most related to acute rupture or erosion. However, the calcium isn’t necessarily the factor contributing to plaque instability.

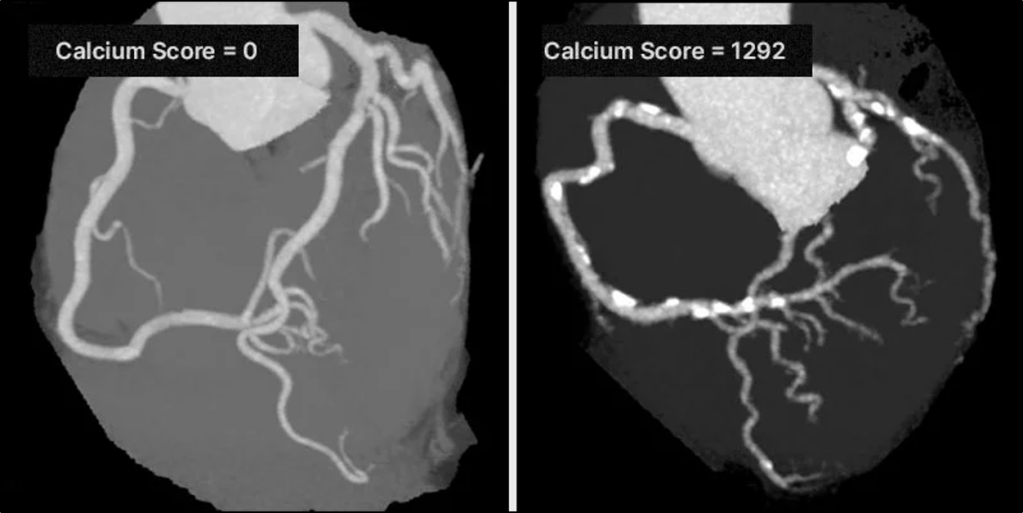

On the other hand, macrocalcifications are large, sheet-like calcium deposits, often exceeding 1 mm in size. These are usually seen in advanced plaques and are associated with a healing response to chronic inflammation. In all kinds of arteries, macrocalcification is a hallmark of stable plaques. In a histopathological analysis of coronary arteries, acute thrombotic lesions displayed much less calcification, while fibrocalcific plaques and healed plaque ruptures showed maximum calcification. Ossification, the process of bone formation, signifies the conclusion of the reparative process and is linked to a state of quiescence, absence of inflammation, and a significantly lower likelihood of acute rupture. Of note, the calcification areas visible on coronary artery calcium CT likely represent safer zones, while the more fragile microcalcifications actually go undetected.

Since calcium is an essential component of bone, it is perhaps not surprising to learn that people with vascular calcification have lower bone mineral density and a higher risk of fractures, since it’s being deposited in the blood rather than bone. However, the dynamic is much more complex than that, and there’s an overlapping of molecular pathways and risk factors between vascular calcification and osteoporosis that contributes to this finding.

Take Home Points:

- Vascular calcification begins as a response to chronic inflammation.

- Vascular calcification involves the transformation of vascular smooth muscle cells to osteoblasts.

- Microcalcifications, which are hard to see on conventional CT, represent areas of increased risk. Macrocalcifications, which can more easily be seen on CT, represent areas less prone to rupture.

Listen to the episode!

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Tony Breu

◾️Show notes written by Tony Breu and Millennium Manna

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Breu AC, Abrams HR, Buonomo G, Cooper AZ, Manna M. From Vessel to Bone. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. August 6th, 2025.

Image Credit: News from Karolinska Institutet