Why was iodine given to people exposed to radioactivity after Chernobyl?

Chernobyl. Even those who don’t actually know where it is or what happened there use the word as a metaphor for catastrophe and irrevocable destruction. At 1:23 in the morning on April 26, 1986, in the northern Ukranian city of Pripyat, a nuclear power plant called Chernobyl exploded and sent an enormous radioactive plume into the atmosphere, spreading radiation for hundreds of miles. You may be wondering why we’re discussing a famous disaster on a medical podcast. As the radiation spread, one of the first public health actions taken was to distribute iodine tablets and solutions to people in its path. Why did they do this?

Even if you’ve seen the HBO mini-series, knowing a bit about how the disaster happened is helpful. Nuclear reactors need to be constantly cooled to function, and early that April morning the power plant engineers were running a safety check on Reactor 4 to see if it could withstand a temporary loss of power and therefore temperature regulation. How exactly it happened is complex, but the basic facts are that over a long safety check with personnel shift changes and faulty equipment, the reactor reached a critical temperature and exploded. Someone fishing nearby in a pond reported seeing this eerie blue haze shooting up into the sky, the effects of an enormous blast of radionuclides that were ionizing nitrogen and oxygen atoms in the air all around the reactor, specifically iodine-131, caesium-134 and caesium-137. The protective lid above the reactor literally blew off because of the force of the explosion and released all of this radioactivity into the atmosphere, spreading over not just Ukraine but large swaths of Russia and Eastern Europe.

28 people died soon after of acute radiation poisoning. But millions of people across Eastern Europe were exposed to the isotopes, both from breathing in the toxic air and then eating food and drinking milk which had been produced in radioactive soil, even months after the disaster. These are the people who iodine helped to save. How exactly did that help?

The answer, surprisingly, has to do with preventing thyroid cancer. Over 6000 cases were linked to radiation exposure, with a dose-response relationship between how much radiation someone was exposed to and their risk of developing thyroid cancer. Many more cases would probably have developed if public-health officials hadn’t rushed to distribute iodine to millions of people after the disaster. Iodine works, essentially, by preventing the thyroid from absorbing radiation, and therefore from accumulating the cellular damage that leads to tumors.

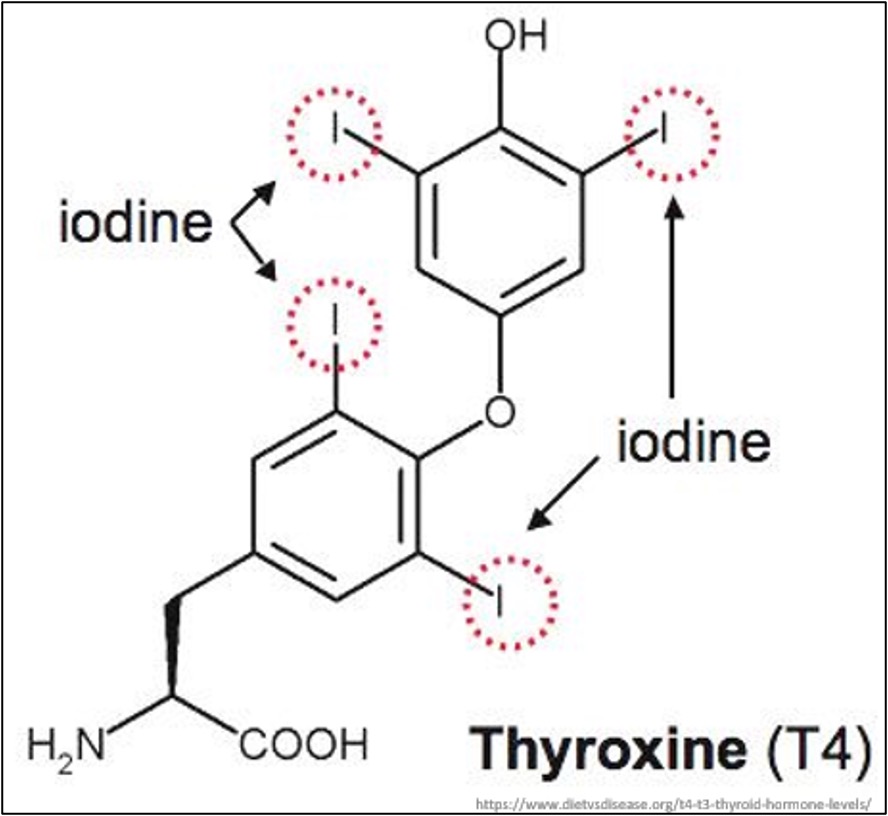

Iodine doesn’t usually get the same attention as potassium or magnesium, but it’s an essential micronutrient, meaning the body can’t produce it (which is why table salt is often iodized). T3 and T4, the main thyroid hormones, contain iodine. The thyroid ends up absorbing much of the iodine we eat to make them, using a specialized natrium iodide symporter. When people breathed or ingested the iodine-131 from the Chernobyl cloud, their thyroid’s couldn’t distinguish it from “normal” iodine, which put that organ at unique risk of harm.

Enter something you probably haven’t heard since medical school: The Wolff-Chaikoff effect. It’s named after two biochemists,Jan Wolff and Israel Lyon Chaikoff, who observed this effect back in 1948 at UC Berkeley. When they gave that radioactive iodine-131 isotope to rats, iodine uptake into their thyroids nearly completely stopped once the serum iodine level rose by 20-35%, and then quickly resumed again once the iodine levels returned to baseline. They wrote in their paper: “These results, therefore, suggest that plasma inorganic iodine acts as a homeostatic regulator in the formation of the thyroid hormone. This regulator probably serves to prevent the formation of excessive amounts of hormone by the gland when the body is suddenly flooded with iodine.” In other words, if the thyroid starts absorbing too much iodine, it shuts the symporters down to prevent excess thyroid hormone production. In fact, iodine-131 (in very controlled doses) is still used to treat certain thyroid cancers and hyperthyroid disorders.

The iodine distributed after Chernobyl was a very simple, but elegant, way to protect people from thyroid cancer. By ingesting large doses of “normal” iodine, their thyroids couldn’t absorb as much radioactive iodine. In experimental models, just 100mg of potassium iodide lead to a 95% reduction in radioactive iodine uptake, with subsequent 15mg of daily consumption keeping absorption to less than 10%. It’s impossible to say how much iodine helps in a Chernobyl situation, where the amount and duration of radiation exposure is quite variable, but one paper estimates that it reduces thyroid radiation absorption by at least 40%.

Like Pompei, Pripyat is frozen in time. Thousands of people fled in 1986 and could never return, the town forever poisoned with radiation. As the buildings crumble and plants grow everywhere, papers are still strewn on school desks and an amusement park still has a rusting ferris wheel. Chernobyl itself was sealed in a sarcophagus of steel and concrete. The area is so toxic that a new substance has been identified, a compound of zirconium silicate crystals and uranium fittingly named Chernobylite. No amount of iodine can ever make that better.

Take Home Points

- Radioactive iodine-131 was one of the isotopes released from the Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986

- One of the first public health responses involved mass distribution of iodine pills

- This was done to protect against thyroid cancer via the Wolff-Chaikoff effect, whereby flooding the thyroid with iodine leads to a temporary shutdown in iodine into the gland

Sponsor

This episode was sponsored by FIGS. FIGS is offering 15% off your first purchase. Just go to wearfigs.com and use the code FIGSRX at checkout

https://directory.libsyn.com/episode/index/id/37524280

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Avi Cooper

◾️Show notes written by Avi Cooper and Giancarlo Buonomo

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Cooper AZ, Abrams HR, Breu AC, Buonomo G, Manna, M. Wherefore Iodine?. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. July 23rd, 2025.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons