Why do we worry about Pseudomonas in diabetic foot infections?

One of the age-old challenges of medicine is deciding which infections to suspect in which patients based on which risk factors. Everything from whether a patient has an artificial joint to if their cat recently scratched them can be meaningful when making a diagnosis. Some of the associations make intuitive sense – someone in Burundi is more likely to get malaria than someone in Buffalo. There’s one association propagated in the hospital, though, which is not so intuitive. When patients with a suspected diabetic foot infection (DFI) present, they often receive empiric coverage against Pseudomonas. Why are we so worried about Pseudomonas in DFI, and should we really be?

When we say “Pseudomonas” in medicine, we’re usually talking about Pseudomonas Aeruginosa, a gram-negative, rod-shaped bacterium that tends to live in water, particularly fresh water, and soil. It can cause many different infections, including some mild ones like otitis externa (“swimmer’s ear”). However, Pseudomonas is most notorious for antibiotic resistance and causing potentially fatal infections, particularly in healthcare settings. Some of the main risk factors for Pseudomonas infection include recent hospitalizations, recent antibiotic exposures, immuno-compromise, known Pseudomonas colonization, or certain pre-existing conditions like cystic fibrosis or structural lung disease. For these reasons, any suspected diagnosis of ventilator-associated pneumonia or febrile neutropenia warrants automatic Pseudomonas coverage.

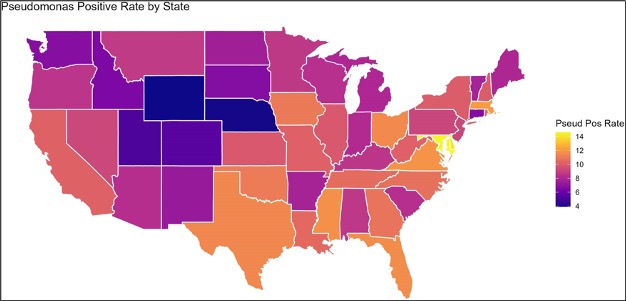

Diabetes is not, in and of itself, a risk factor for all types of Pseudomonas infections. In fact, it’s not necessarily a risk factor for Pseudomonas foot infections. According to the official Infectious Disease Society of America guidelines, empiric Pseudomonas coverage is not recommended for suspected DFI in North America or Western Europe (in the absence of other clear risk factors). The guidelines reflect, at least in the USA, how low rates of Pseudomonas actually are in DFI. One meta-analysis puts the prevalence around 8% (with the caveat that the researchers didn’t specify how samples were obtained). The overall global prevalence is higher, estimated at 11% and virtually tied for the 2nd-most common culprit in DFI. Even in the USA there’s geographic variation. A study from diverse Veteran’s Affairs medical centers tracked DFI data and found that in areas marked as “cool/dry,” prevalence was only 6.4%, whereas in “hot/humid” places, it went all the way up to 11.6%.

It’s clear that Pseudomonas is far less prevalent in the USA, even in the muggiest places, than most medical professionals realize. One multi-center trial studied DFI in 292 patients and it too found that only around 9% of patients ended up having Pseudomonas. However, 88% of all patients had gotten empiric Pseudomonas coverage. Furthermore, there was no difference, retrospectively, in empiric coverage between those who did and didn’t have Pseudomonas. Now, the number covered for a bug is always higher than the number actually infected (that’s the whole point of empirical antibiotics). But this nearly ten-fold difference suggests a major gap between the perceived and actual prevalence of Pseudomonas in DFI.

There may even be a gap between the prevalence and pathogenicity of Pseudomonas in DFI. A 2005 study published in The Lancet compared the empiric treatment of DFI with ertapenem (which doesn’t cover Pseudomonas) versus piperacillin/tazobactam (which does). The results were quite surprising – not only was there no difference in outcomes between the treatment groups, but patients who eventually had Pseudomonas isolated from their wounds did just as well with ertapenem. Either Pseudomonas is susceptible to ertapenem in ways we don’t understand, or its presence in an infected wound doesn’t automatically make it the one driving the infection.

We haven’t really answered whether, even if the absolute risk is lower than one may have thought, whether patients with diabetes are more likely to get Pseudomonas compared to those without diabetes. There is no “smoking gun” study that shows higher rates of Pseudomonas infection in DFI vs other, non-diabetic foot infections. One study did compare foot infections in diabetic vs non-diabetic patients, and although the culprit pathogens weren’t identified, the diabetes group had worse rates of severe infection, re-infection and healing time. These results are what one would expect, as diabetes is linked to everything from microvascular damage to diminished immune responses to poor wound healing. These are all reasons why patients with diabetes are so prone to developing ulcers, which initially form from excess pressure on neurologically-damaged areas, and gradually enlargen into deep, chronic wounds full of necrotic tissue.

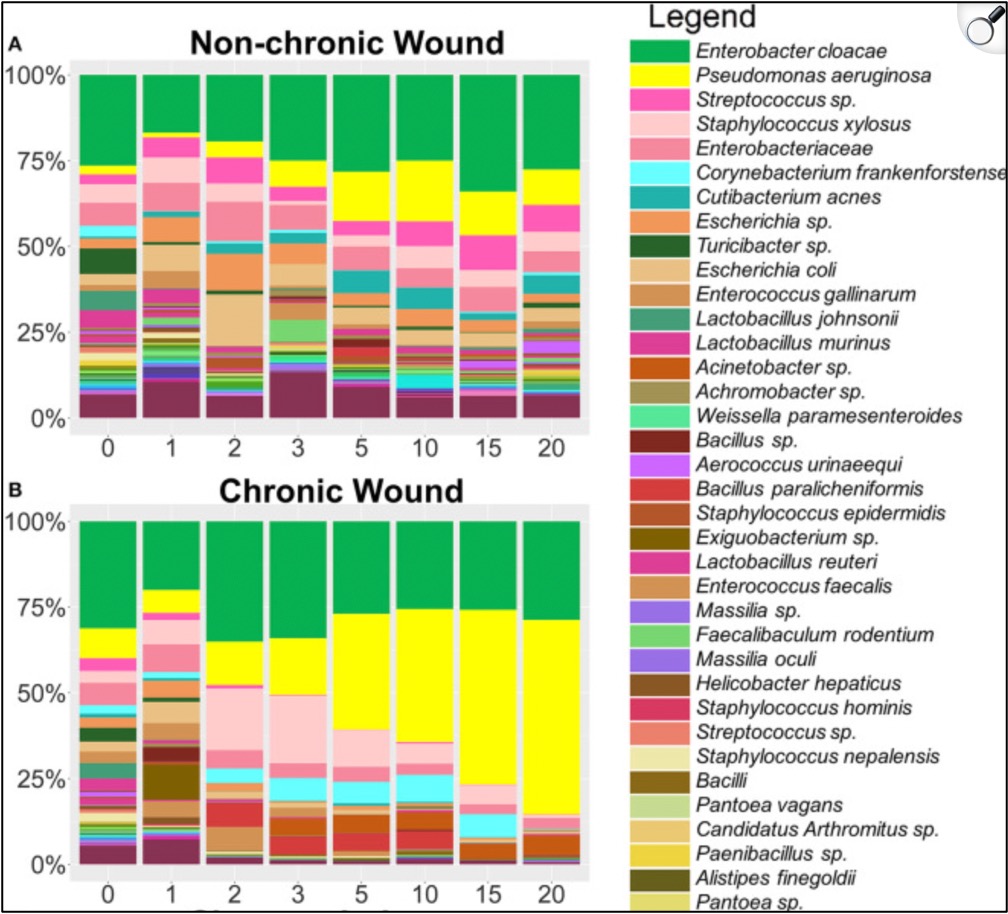

Is that the whole story then? Patients with diabetes aren’t really more likely to get Pseudomonas so much as they are more likely to develop chronic wounds, particularly on the lower extremities, and if there’s Pseudomonas in the water or soil, a wound on the foot is the first place they’ll swim into? That’s part of the story (which is why Pseudomonas infection in DFI’s seems so geography-dependent). However, there’s good in-vitro evidence to support the claim that patients with diabetes may actually be more susceptible than others to Pseudomonas infection. One study took mice bred to have diabetes and gave them all small wounds, except that half of them were left to heal on their own, and half were given antioxidant-enzyme inhibitors, to create the high oxidative stress characteristic of a chronic wound. Each mouse was then swabbed for bacterial colonization multiple times over the next 20 days. In the “non-chronic” wounds, the microbiota remained relatively diverse and stable, whereas in the “chronic” wounds, the diversity decreased in favor of biofilm-forming species, most notably Pseudomonas, where on average it was forming >50% of the total bacterial population. There were some Pseudomonas in non-chronic wounds, but at much lower levels and without biofilms.

One could argue that the above-mentioned study is evidence more that chronic wounds, not diabetes itself, is the Pseudomonas risk factor. Another study, though, deliberately infected mice with Pseudomonas, but this time one group had diabetes and the other didn’t. The mice with diabetes had over five times the biofilm production, as well as longer healing times and worsened response to gentamicin.

So are patients with diabetes at a greater risk of Pseudomonas foot infections? Probably. The data indicates that patients with diabetes are at a greater risk of chronic wounds, that chronic wounds are highly hospitable to Pseudomonas, and diabetes may make clearing Pseudomonas more difficult. Is the overall risk of Pseudomonas infection lower than many American healthcare workers think? Probably. Just some things to keep in mind when deciding which antibiotics to use when treating a DFI!

Take Home Points

- Diabetes is not, in and of itself, a risk factor for all types of Pseudomonas infections. However, there are several plausible reasons why diabetic foot ulcers may be particularly at risk, including:

- High oxidative stress in chronic wounds, which Pseudomonas can thrive in compared to other organisms

- Poor immune response, leading to reduced clearance of Pseudomonas biofilms

- The actual prevalence of Pseudomonas in diabetic foot infections in the USA is far lower than most clinicians realize, although the prevalence is higher elsewhere in the world

- Diabetic foot infections that grow Pseudomonas respond equally well to antibiotics without Pseudomonas coverage, which indicates that the presence of Pseudomonas in wounds is not necessarily pathologic

Listen to the episode!

https://directory.libsyn.com/episode/index/id/35061500

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Sponsor

Freed is an AI scribe that listens, transcribes, and writes medical documentation for you. Freed is a solution that could help alleviate the daily burden of overworked clinicians everywhere. It turns clinicians’ patient conversations into accurate documentation – instantly. There’s no training time, no onboarding, and no extra mental burden. All the magic happens in just a few clicks, so clinicians can spend less energy on charting and more time on doing what they do best. Learn more about the AI scribe that clinicians love most today! Use code: CURIOUS50 to get $50 off your first month of Freed!

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Giancarlo Buonomo

◾️Show notes written by Giancarlo Buonomo

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Buonomo G, Abrams HR, Breu AC, Abrams HR, Cooper AZ. A Pseudo- truth? The Curious Clinicians Podcast. January 22nd, 2025.

Image Credit: Glencoe Regional Health Center