Why don’t we administer insulin orally?

In inpatient medicine, a phrase one often hears is “transition to PO.” Medications that start out as injections or infusions – antibiotics, steroids, anticoagulants – are switched to an oral equivalent as soon as possible. There’s one drug, though, which we never talk about taking in pill form. Insulin is one of the oldest and most widely-used remedies that we have. So why can’t we administer it orally?

First, a little primer on the history of insulin. In 1921 at the University of Toronto, Frederick Banting, a 30-year-old orthopedic surgeon, approached experienced physiologist John Macleod about isolating pancreatic extracts to lower blood glucose. Macleod set him up with a lab and and a partner, medical student Charles Best. This unlikely pairing began their experiments in May, and in December were joined by James Collip to assist with purifying. In January of 1922, they injected their extract into Leonard Thompson, a 14-year-old boy with diabetes, observing a 25% reduction in blood glucose.

It’s hard to overstate this discovery. After treating Thompson for another month, Banting and Best published their animal data, followed quickly by Thompson’s case study. A year later, Banting and Macleod won the Nobel prize (Best’s exclusion in favor of Macleod would irritate him for the rest of his life). Two years of research and one patient treated would be unheard of nowadays for a Nobel, but their achievement was just too important.

Banting and Best didn’t know everything about insulin in 1922, but they knew it couldn’t be administered orally. That stands today – insulin is given subcutaneously, or occasionally intravenously. What is it about insulin that makes an oral route untenable?

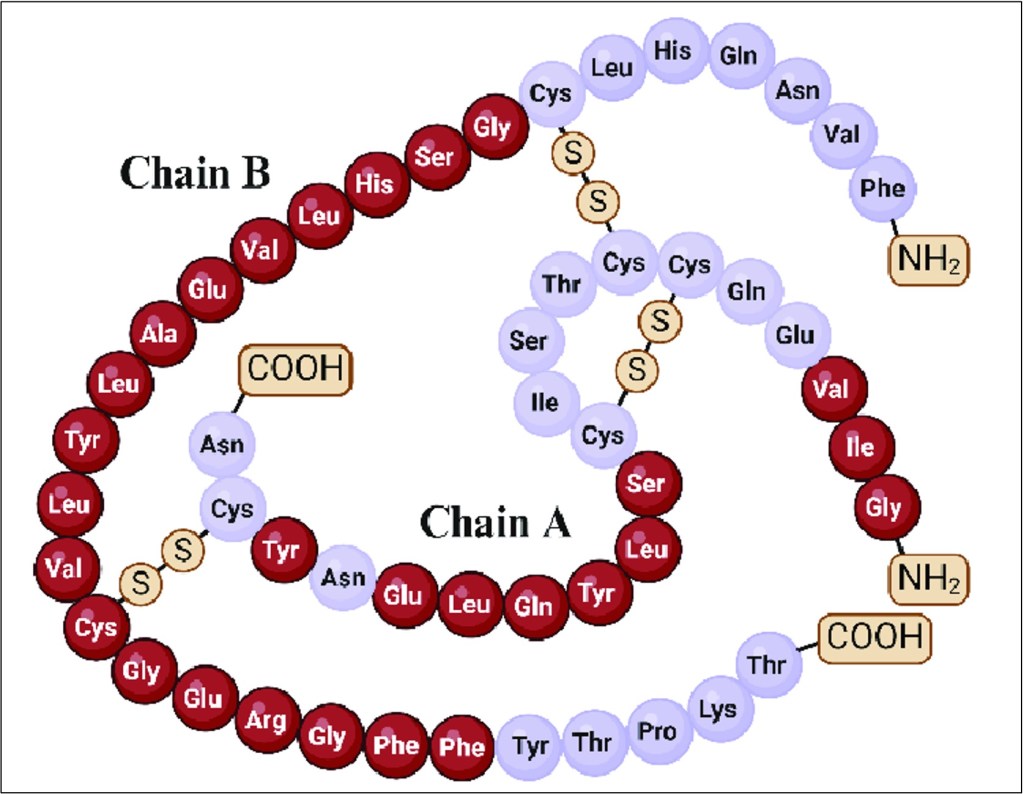

One big reason is that insulin is … big. It’s composed of 51 amino acids and weighs in at 5.8 kD (technically, >50 amino acids makes it a protein, but most call it a peptide). This large size leads to poor absorption – molecules greater than about 700 Daltons (0.7 kD) are not well absorbed. Small peptides like octreotide (8 amino acids, 1 kD) can have oral formulations. For the most part, though, large peptides like insulin and even larger proteins like IVIG and albumin must be administered with injections or infusions to get absorbed.

To be clear, we’re talking about insulin being absorbed intact. As a string of amino acids, there’s very little difference to the digestive system between insulin and a piece of steak – it all gets broken down. Within a few years of the discovery and use of insulin in the early 1920s, Harold Dudley reported that pepsin and trypsin (two major proteolytic enzymes of the digestive system) can digest insulin. Even if insulin were smaller, very little of it would pass into the bloodstream with its original structure. To make things even more difficult, the insulin that does get absorbed has a half-life of around 10 minutes. Insulin undergoes proteolysis in the blood, and is also small enough to be filtered by the glomerulus.

It’s no surprise, then, that peptide medications only make up 1-2% of the medications sold in America. Drugs like ACTH or calcitonin have to be given via injection or IV, making them less widely and frequently consumed than something like an antihypertensive.

However, one might note that although the number of peptide medications sold is increasing ( and projected to keep doing so), especially in the form of GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide (Ozempic), which has an oral formulation. Semaglutide isn’t quite as big as insulin (4.1 kD), but certainly higher than that 0.7 kD threshold. Why can it be administered orally but insulin can’t? Oral semaglutide is packaged with salcaprozate sodium, or SNAC. This compound aids in two ways. First, it protects against degradation by proteolytic enzymes. Second, it acts as a”permeation enhancer” by either promoting trans-cellular absorption or modifying cell-cell adhesion to aid in para-cellular absoprtion.

Insulin has not fared well in proof-of-concept studies for combination with SNAC – the more that is added, the less efficiently the absorbed insulin is able to lower glucose. However, that doesn’t mean hope is lost for oral insulin. One proposed solution is inspired by the unlikeliest source: Squid. A recent paper in Nature has the marvelous title of “Cephalopod-inspired jetting devices for gastrointestinal drug delivery.” The researchers designed a microscopic delivery system that “injects” the drug into the stomach lining using tiny jet streams, in the same way that squid and other cephalopods jet-propel ink into their surroundings when threatened. When insulin and GLP-1 medications were given to pigs with the micro-jet device, their serum levels of the drugs were comparable to subcutaneous administration.

Other ideas are a little more theoretical, ranging from nanoparticles to protective hydrogels to “zwitterionic micelles,” where insulin is encased in a neutrally-charged, viral-mimetic shell that can pass through the mucosa and epithelium without opening tight junctions. The larger point, though, is that after more than a century, oral insulin may one day prove to be a viable alternative to the injected form.

Take Home Points

- As a peptide, insulin undergoes proteolytic degradation in the GI tract and blood

- Insulin is also a pretty large peptide, limiting its absorption

- These factors make oral insulin tough to engineer. But, that may change. Stay tuned!

Listen to the episode!

https://directory.libsyn.com/episode/index/id/34774835

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Sponsor

Freed is an AI scribe that listens, transcribes, and writes medical documentation for you. Freed is a solution that could help alleviate the daily burden of overworked clinicians everywhere. It turns clinicians’ patient conversations into accurate documentation – instantly. There’s no training time, no onboarding, and no extra mental burden. All the magic happens in just a few clicks, so clinicians can spend less energy on charting and more time on doing what they do best. Learn more about the AI scribe that clinicians love most today! Use code: CURIOUS50 to get $50 off your first month of Freed!

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Tony Breu

◾️Show notes written by Giancarlo Buonomo and Tony Breu

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Breu AC, Abrams HR, Cooper AZ,, Buonomo G. Oral Argument. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. January 8th, 2025.

Image Credit: SurgiMac