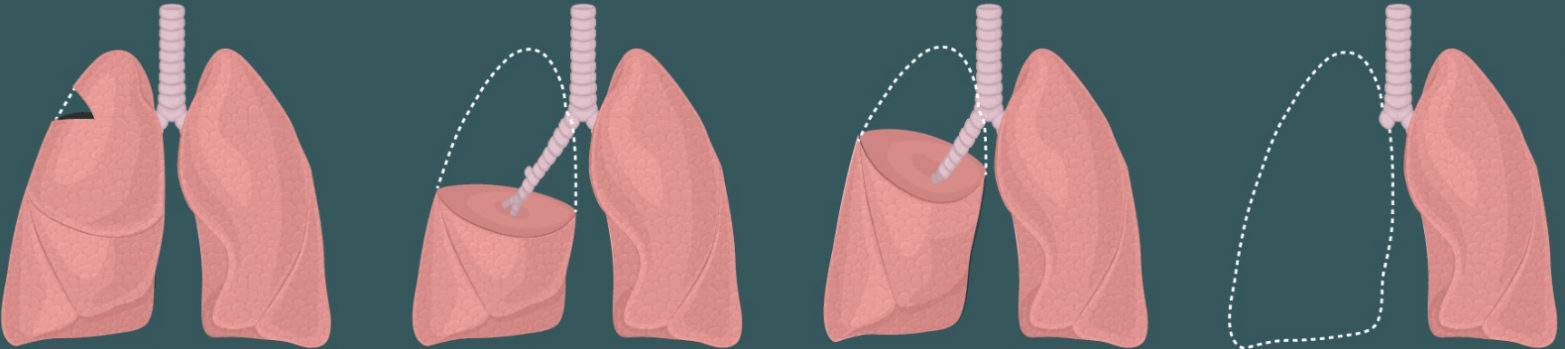

How could you live with only one lung?

The math seems simple. If you only have one lung, you only have 50% of your normal lung function, you can only get 50% of the normal amount of oxygen into your blood, and you’ll be dead in a few minutes. However, there are many patients who undergo pneumonectomies and not only survive, but don’t need supplemental oxygen and even can exercise. How is this possible?

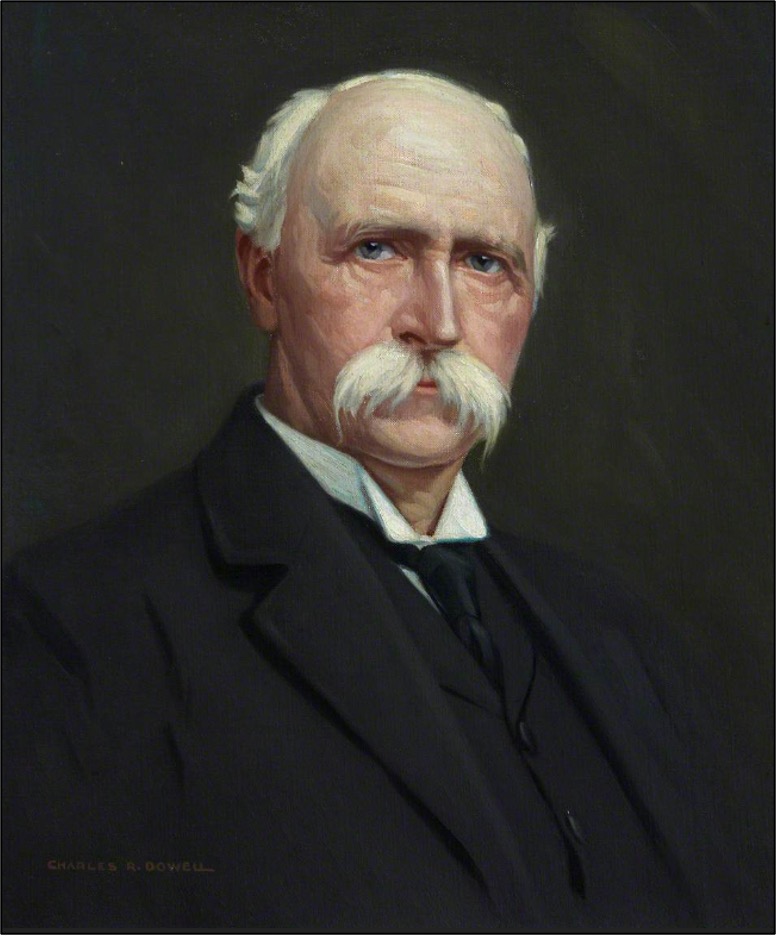

The first pneumonectomy was performed in 1895 by William Macewen, who looked exactly as one would expect a pioneering Victorian-era surgeon to look. Macewen is responsible for numerous innovations that are still used today, such as performing the first bone graft, the first brain tumor removal, the first endotracheal intubation, and most relevant for this episode, the first pneumonectomy.

In 1895, a porter called R.W. presented to Macewen after 3 years of progressively worsening symptoms, including fever, dyspnea on exertion, pain and swelling in his left chest, and a suffocating feeling when he lay on his right side. Macewen deduced that he had tuberculosis, which had necrotized most of his left lung and the pleural lining, which was then filled with a secondary bacterial empyema. With no imaging available to him (the X-Ray was only discovered that very year), Macewen did what he knew best – he operated. Puncturing R.W.’s left hemithorax produced a rush of purulence and, seeing that there was nothing salvageable, Macewen proceeded to remove the remnants of his left lung over two separate sessions. R.W. followed up with Macewen for years, and in 1906, was still working as a porter and could walk 10 miles at a time. Macewen even noted that R.W. could climb the 80 stairs to his clinic office and not arrive out of breath.

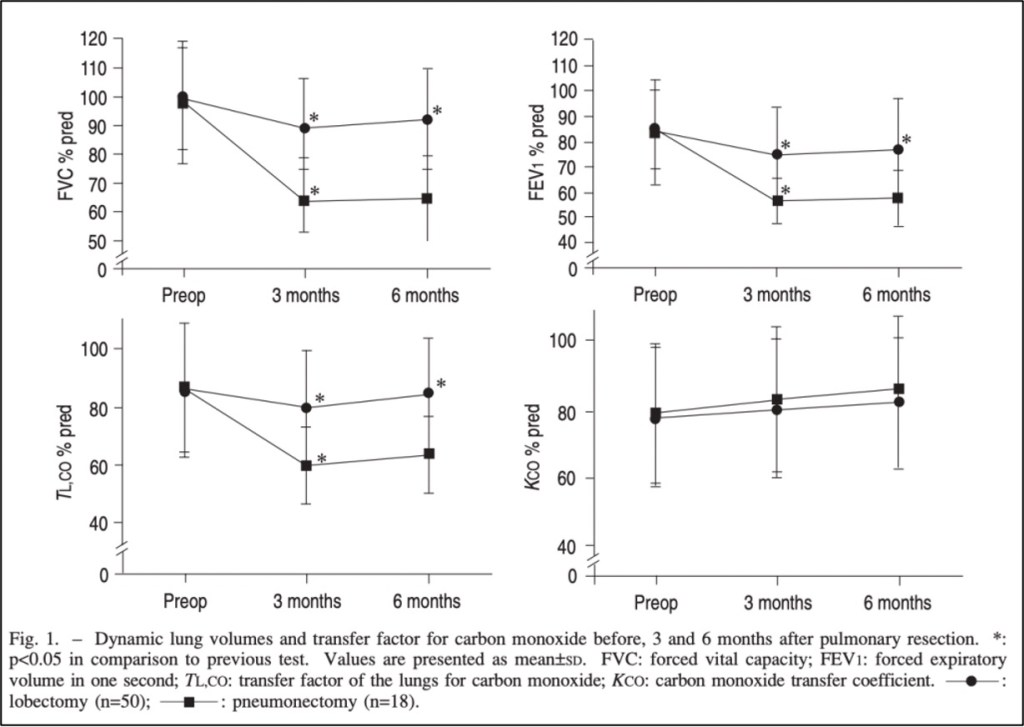

This was no crude solution forced by crude medical knowledge. To this day, pneumonectomies are still regularly performed for a variety of reasons, such as removal of advanced lung cancer. But the question still remains: How can one survive with just one lung? To address the “math” mentioned at the beginning, it turns out that it’s not that simple. In one study that followed patients six months post-pneumonectomy, there was an average decrease of 32-36% in FEV1, FVC, and DLCO and a 20% in VO2 max. Substantial decreases of course (and significantly more than patients who just underwent a lobectomy) but far from the 50% one might expect.

As the pulmonologist James Allen once said, we’re all born with 25% more lung than we actually need. Much like we talked about in our hemoglobin episode, the body starts out at a physiological surplus that it can then tap into. It makes sense, then, that maximum exercise is almost always limited by heart rate rather than pulmonary capacity.

When the body loses an entire lung (as opposed to having an intact, but malfunctioning one), ventilation and perfusion can be maximized in the remaining lung. Since all tidal volume is now going to one lung, previously-atelectatic segements, particularly at the bases, get opened. These alveoli then stay open, which increases the potential surface area for gas exchange. This overall increase in ventilation (V) is accompanied by an increase in perfusion (Q), as all cardiac output is to one lung, meaning there is no V/Q mismatch.

Most amazing of all, though, is that the remaining lung may actually grow new tissue. After her 1995 right pneumonectomy, researchers followed a patient for the next 15 years. In the few years after surgery, her left lung increased in size and TLC, but decreased in density, which would be expected with increased alveolar recruitment and lung hyperinflation. However, over the net decade, her lung doubled in size (even expanding into her empty right chesty cavity), but the density didn’t change. This implied that the continued growth was from new tissue, rather than inflation.

How exactly this new growth occurs isn’t clear. There must be some initial signal for the lung to start growing. It may be stretch-induced, as the lung is getting distended by the doubling of tidal volume. Whatever that signal is, it must go to resident pulmonary stem cells (like type II alveolar cells) to stimulate a rapid initial growth of new alveoli. This is then followed by a more gradual phase of tissue remodeling and angiogenesis so that the new alveoli can be adequately ventilated and perfused.

Although taking place on a much larger scale, this post-pneumonectomy tissue growth is a process that normal lungs do constantly to repair themselves from the wear-and-tear of daily life. In fact, there is a growing movement to think of COPD and other structural lung diseases as being driven by a failure of this normal lung regeneration, which explains why they are so much more common in older people whose repair mechanisms have slowed down.

Take Home Points

- Humans are able to tolerate pneumonectomy for two main reasons

- The first is that the remnant lung taps into innate excess functional capacity, in particular by alveolar distention and recruitment, and improved VQ matching. This is more immediate.

- The second is compensatory lung growth, which is driven by stem cells, and is effectively a form of regeneration but really can be thought of an injury response due to higher lung volumes going to the one remnant lung. This slow growth takes place over the course of years.

- Emphysema and fibrotic lung diseases may reflect a failure of proper lung regeneration in response to injury

Listen to the episode!

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Avi Cooper

◾️Show notes written by Giancarlo Buonomo and Avi Cooper

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Cooper AZ,Abrams HR, Breu AC, Buonomo G. Living on a Lung. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. October 30th, 2024.

Image Credit: Lung Cancer Center