Why do hot flashes occur?

What’s something that people going through menopause have in common with people getting treatment for breast or prostate cancer? Hot flashes. But what are they, exactly? And why do they happen? In this episode, we’ll take a tour around the body and deep into the brain to answer both questions.

Hot flashes occur in over 50% of people going through menopause. They are what the name suggests – sudden onset feelings of warmth, flushing and sweating. While not painful, per se, they can be incredibly unpleasant and affect quality of life, in part because they can happen so frequently. In fact, hot flashes are the most common menopause-related reason people in menopause seek medical attention.

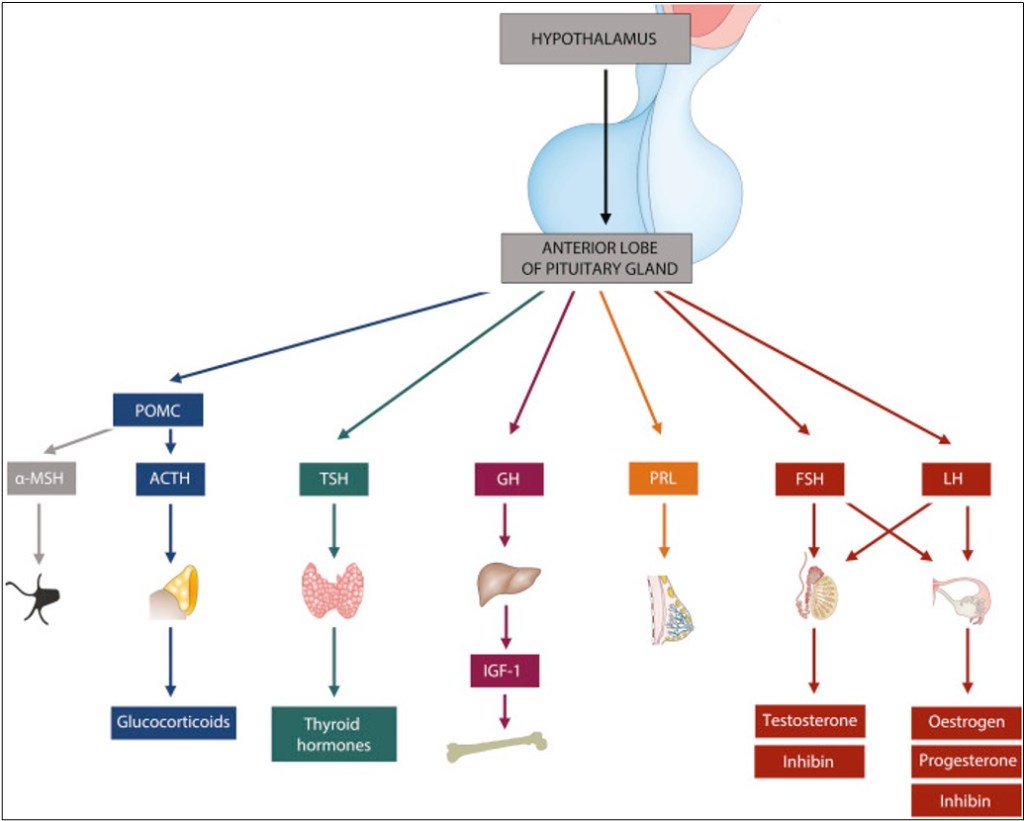

Hot flashes are grouped under the umbrella term “vasomotor symptoms,” which are caused by vasoconstriction or dilation. Hot flashes are the latter. As the blood vessels dilate, heat travels to the skin surface, creating a sensation of warmth. Unlike fever, though, core body temperature actually drops. That part of the mechanism is simple enough, but what actually causes the blood vessels to dilate is a little more complex. It all starts with the hypothalamus and pituitary. Generally, the way the endocrine system works is that the hypothalamus produces a “releasing” hormone, which stimulates the hypothalamus to produce a “stimulating” hormone, which in turn activates the target gland to produce the actual hormone. For example, in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) causes the release of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), which act on the ovaries and testes to result in the release of estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone.

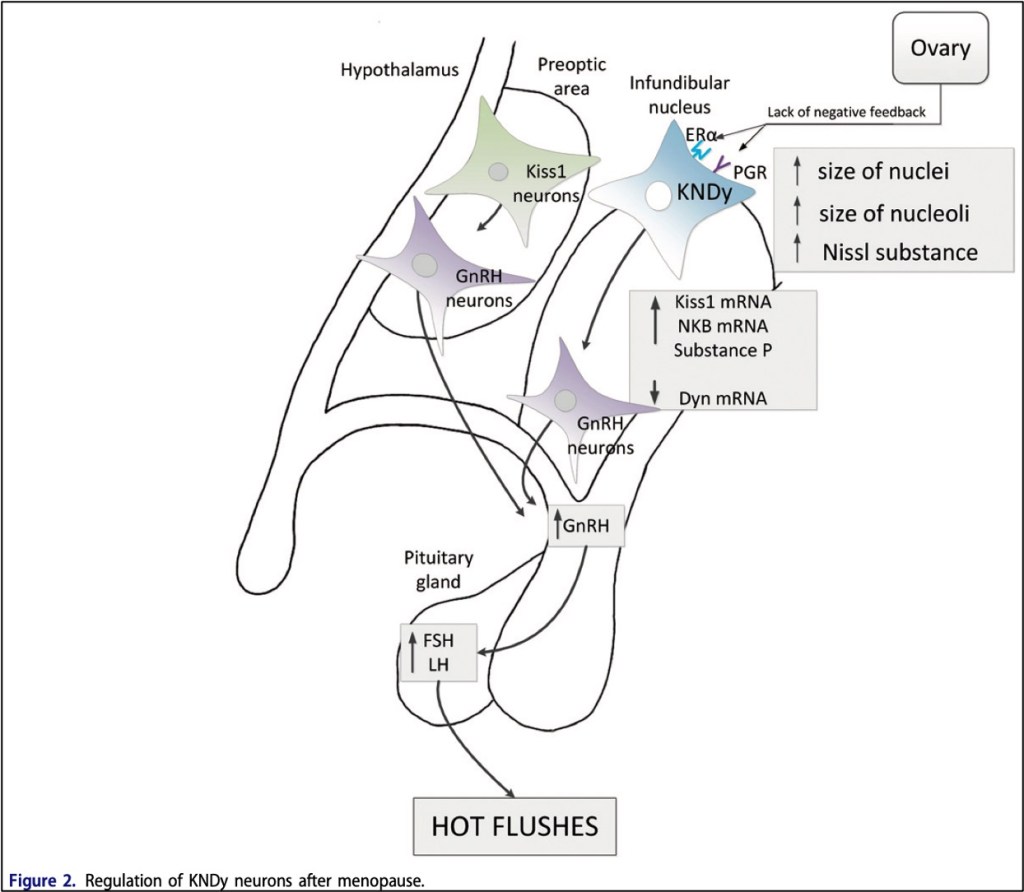

The above-mentioned axis is the one we will focus on because it, unsurprisingly, is the one most affected by treatments for prostate and breast cancer. Like most other endocrine axes, the HPG axis self-regulates through negative feedback: As sex hormone levels rise, they suppress the production of GnRH, LH, and FSH, which keeps sex hormones at appropriate physiological levels. GnRH usually has a consistent, pulsatile release from the GnRH neurons of the hypothalamus. These neurons are regulated by two others, called Kiss1 (in the preoptic area) and KNDy (in the infundibular nucleus). The former just secretes kisspeptin, which stimulates the GnRH neurons. The latter not only secretes kisspeptin, but also neurokinin and dynorphin (hence, K-N-Dy). The “N” and the “Dy” act as a gas pedal and a brake, respectively, on the KNDy neuron, and their levels are also influenced by how total-body levels of estrogen and progesterone.

When people go through menopause, the ovaries produce less estrogen and progesterone. As sex hormone levels drop, the HPG axis has no negative feedback, and the KNDy neurons hypertropy. They produce more of the neurokinin B and overall less dynorphin, causing a feedback cycle of growth for the cells. The GnRH neurons get stimulated more, leading to a loss of pulsatility and an overall increase in GnRH, which then leads to an increase in FSH and LH.

Why do hot flashes happen as the HPG axis changes? Surges in LH are associated with hot flashes, but LH itself may not be the only cause. This is supported by the observation that in women who have had their pituitary glands removed and are receiving estrogen supplementation, withdrawal of estrogen still leads to hot flashes, despite them not producing any LH. One hypothesis is that the hypertrophied KDNy neurons begin to affect the adjacent thermoregulatory centers in hypothalamus. In one study where neurokinin B (the “gas pedal” compound) was injected into subjects who were all in the same phase in the menstrual cycle, they had more hot flashes than those who got no NKB. Hot flashes are also associated with variants in the neurokinin B receptor gene.

That hot flashes are dependent on an unregulated HPG axis is perhaps best demonstrated by examples of disorders where hot flashes DON’T occur. In Kallmann syndrome, the GnRH neurons fail to migrate correctly from the olfactory bulb to the hypothalamus, which classically leads to loss of smell and delayed puberty. These patients have low sex hormone levels, but because they also don’t have the LH-producing section of the hypothalamus, they don’t have hot flashes. Likewise, patients with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea have low estrogen, but no hot flashes, because weight loss or stress actually causes low GnRH and therefore LH levels.

One could ask whether hot flashes are just an inevitable result of an aging endocrine system, or one altered to treat cancer. There are some theories that hot flashes actually have an evolutionary basis such as an increased need for thermoregulation after childbirth (when estrogen and progesterone also drop) or protection against the cardiovascular diseases for which menopause increases risk. However, these remain just theories.

Perhaps the more interesting question, though, is why hot flashes are, well, “flashes.” If the negative feedback on the HPG axis has been removed, shouldn’t there be constant vasodilation and feelings of warmth? One study showed that directly stimulating the kisspeptin neurons of mice can cause a hot flash. Furthermore, in mice whose ovaries were removed, less stimulation of the kisspeptin neurons was required to produce a hot flash. The researchers theorized in a hypogonadic individual (like someone who is going through menopause, or who is taking HPG-axis-altering therapy for cancer), the kisspeptin neurons are hyper-sensitive and have a low threshold to fire after minor cues like stress, heat or eating spicy food. It’s also been theorized that people in menopause may have a narrower “thermoregulatory null zone”; or euthermic zone, and so might be more sensitive to feeling that thermoregulation is off with slight increase or decrease in temperature.

For patients who do have hot flashes, what treatment can we offer them? It’s clear from the pathophysiology that medications aimed at pain or fever would probably not be helpful. The most logical solution would be hormone supplementation, as it’s the low sex-hormone levels that leads to KDNy hypertrophy. Patients undergoing menopause who have debilitating hot flashes, for example, often get estrogen supplementation. A very wide variety of plant-based compounds have been used for hot flashes over the millenia, including soy, dong quai, red clover, and black cohosh; these are overall thought to work either as phytoestrogens or via modulating serotonin uptake. However, in patients with hormone receptor positive breast cancer (or who are getting estrogen-blocking therapy for cancer in the first place), hormone replacement or phytoestrogens are not safe options. Other attempts have been made with SSRI’s and SNRI’s, as serotonin and norepinephrine may play a role in hot flashes, but there seems to be a large placebo effect.

Other therapies go directly to the source. Dynorphin (the “brake” on KDNy) also acts on K opioid receptors. It’s been shown that K opioid agonists can have a small effect on hot flash symptoms, which is thought due to downregulating that kisspeptin pathway. The most promising new therapy, though, may be fezolinetant, the first neurokinin 3 receptor antagonist approved by the FDA. In a phase-3 clinical trial, average hot flashes per day went from 10 to 4, although a placebo effect was also noted.

Take Home Points

- Hot flashes are a clinical syndrome of flushing, subjective warm temperature, and decrease in core body temperature that are associated with conditions that cause low circulating gonadal hormones, such as menopause or treatment with GnRH agonists.

- Decrease in systemic estrogen causes upregulation in the KNDy and Kiss1 neurons. This lowers the threshold needed to transiently activate GnRH neurons and generate a short LH surge that generates the hot flash symptoms.

- Treatments that alter various points in this pathway have shown efficacy in treating hot flashes, though the mechanisms for many treatments aren’t well understood.

Watch the episode on YouTube!

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Sponsor

Freed is an AI scribe that listens, transcribes, and writes medical documentation for you. Freed is a solution that could help alleviate the daily burden of overworked clinicians everywhere. It turns clinicians’ patient conversations into accurate documentation – instantly. There’s no training time, no onboarding, and no extra mental burden. All the magic happens in just a few clicks, so clinicians can spend less energy on charting and more time on doing what they do best. Learn more about the AI scribe that clinicians love most today! Use code: CURIOUS50 to get $50 off your first month of Freed!

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Hannah Abrams

◾️Show notes written by Giancarlo Buonomo and Hannah Abrams

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Abrams HR, Breu AC, Cooper AZ, Buonomo G,. Flash in the PA. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. July 24, 2024.

Image Credit: Vecteezy