Why do we use IV PPIs to treat acute upper GI bleeds?

Like aspirin for acute coronary syndrome or heparin for pulmonary embolism, IV proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) for upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) are one of those buzzword remedies that everyone learns on their first internal medicine rotation. Bleeding is the most common GI complaint leading to hospitalization, so it’s fair to say that IV PPIs are prescribed all day, every day. But when a therapy is so widespread, it’s easy to stop thinking about why we use it in the first place. On this episode of The Curious Clinicians, we’re asking that question about IV PPIs: Why are they used to treat patients who have acute UGIB?

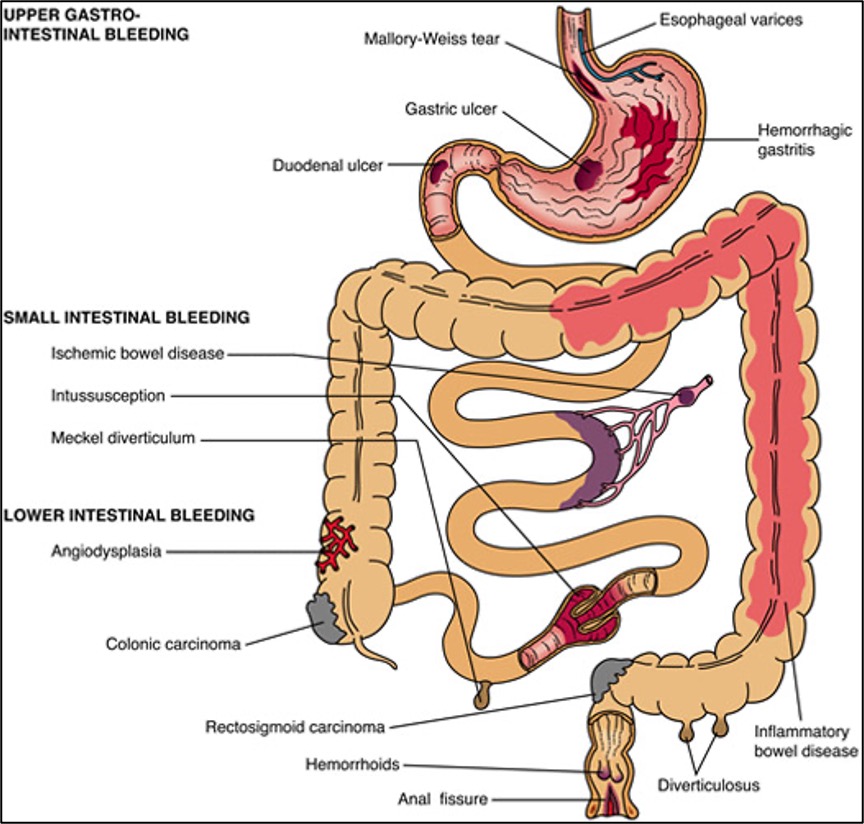

To best answer this question, let’s first review the standard management of a suspected GI bleed. Two important questions to ask yourself are (1) where is this patient bleeding from and (2) how badly are they bleeding? The former is based mostly on symptoms. Technically speaking, an UGIB is bleeding above the ligament of Treitz (located at the junction of the duodenum and jejunum) and patients with melena (black, tarry stools) have a positive likelihood ratio of between 5 and 6 for an UGIB. Blood clots in the stool, on the other hand, are far more likely to be a lower source. However, locating GI bleeds can be tricky because the entire GI tract can bleed and the symptoms are not always precise to one location. For example, a brisk bleed in the stomach can cause bright-red rectal bleeding, while right colon bleeding can cause melena.

Location is important because it often determines intervention. There’d be no point in, say, a colonoscopy for someone who’s clearly having esophageal bleeding. Before intervention, though, we have to answer the second question: How badly is this person bleeding? For UGIB, you can use a clinical calculator like the Glasgow-Blatchford Bleeding Score (GBS) to help determine if someone needs inpatient management. Generally speaking though, someone who is actively bleeding, hemodynamically unstable, or presents with a significant hemoglobin drop is almost definitely getting admitted. Once admitted, patients need to be protected from hemorrhagic shock by getting IV fluids and blood transfusions if necessary while they await diagnosis (and possibly intervention) with endoscopy. It’s at this point that most suspected UGIBs get an IV PPI, although strictly speaking there’s no official recommendation to do so (more on that later).

Peptic ulcers are the most common cause of UGIB, and ~80% of ulcers can be linked back to one of two causes: H.pylori infection or NSAID use. In both cases, mucosal damage, not over-production of stomach acid, is what creates the initial ulcer. In fact, the majority of H.pylori infections raise gastric pH. However, the body’s chronic inflammatory response disrupts the gastric endothelium, which then allows caustic gastric contents to erode down into the vascular supply and cause bleeding. NSAIDS, predictably, do not cause inflammation. Many of them inhibit COX-1, an enzyme that produces prostaglandins that help regulate gastric mucosal blood flow. Inhibiting COX-1 can lead to a loss of mucosal integrity. One study tested this by taking patients who were on chronic NSAID therapy and giving half of them misoprostol, a synthetic prostaglandin. Compared to the control, these patients had 40% fewer GI bleeds.

The relationship between COX-1 and gastric mucosal integrity has led many clinicians to avoid NSAIDS with anti-COX-1 properties in patients at risk for GI bleeding and use only those specific for COX-2, like celecoxib. However, the actual pathophysiology may be more complicated than that. One study gave rats various combinations of NSAIDs, including ketorolac (COX-1 specific) and celecoxib (COX-2 specific). Only rats who received both of them had significant gastric damage. The proposed mechanism is that COX-2 allows for leukocyte adhesion. The larger point, though, is that although gastric acid helps propagate an ulcer, it’s usually not the root cause of one.

One might wonder, then, why we are using IV PPIs in acute UGIB. Patients who have minor peptic ulcer disease often take oral PPIs to help old lesions heal and prevent new ones from propagating. But if someone is acutely bleeding from an ulcer, isn’t it a little late for PPIs? It turns out that the bleeding is exactly what they help with. Acidity has a profound effect on the ability of blood to clot. One study from 1978 took individual blood components from patients and exposed them to progressively lower pH environments in-vitro. When the pH was dropped from 7.4 to 5.9, platelet aggregation virtually ceased, and PT and aPTT were both extended. The authors of the study actually concluded that “this in vitro study may provide a rationale for meticulous regulation of intragastric pH to control upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage.”

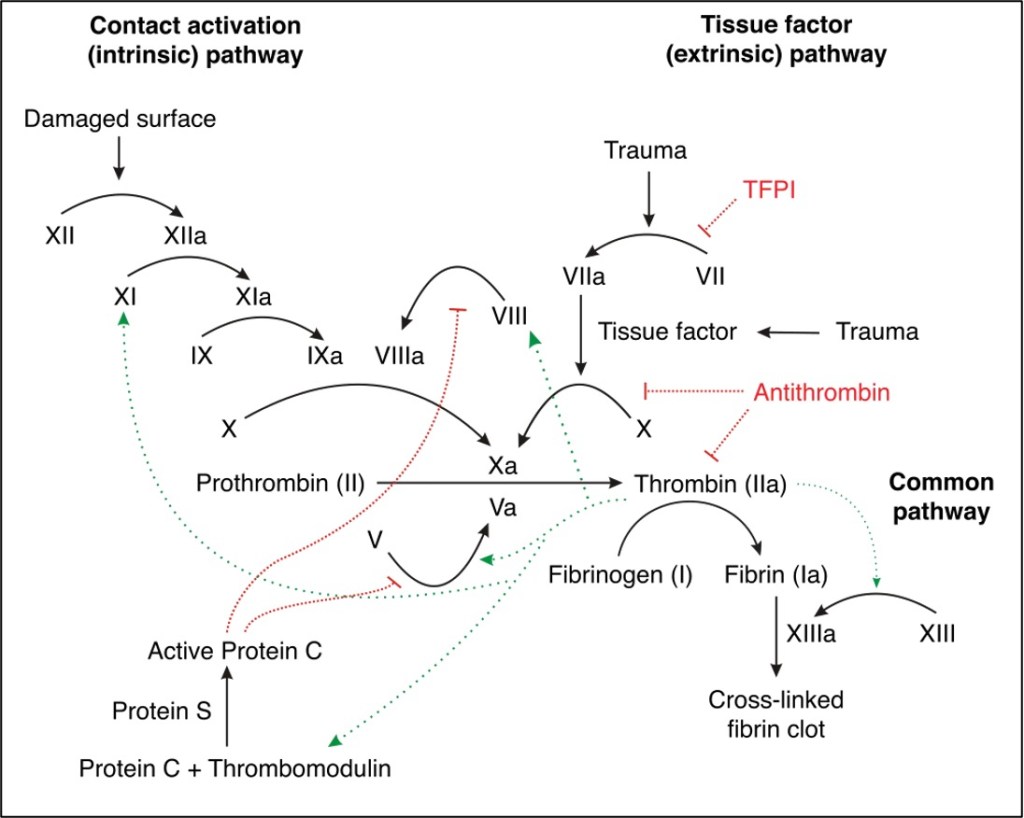

Acid does not affect platelets and coagulation factors in just one way. Coagulation is a complex process that starts when platelets adhere to one another, forming a temporary platelet plug. The coagulation cascade, which is activated both by platelets and by tissue damage, is a series of subsequent reactions where the product of one is the catalyst for the following, which ultimately ends in the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin and the formation of a sturdy fibrin clot. Like most catalysts, coagulation cascade factors are sensitive to external factors like temperature and pH. For example, when pH is reduced from 7.4 to 7.0, the rate at which the FXa/FVa complex activates prothrombin is reduced by around 70%.

However, one study in pigs induced acidosis with hydrochloric acid and then corrected pH with bicarbonate. Despite the correction, coagulation times did not return to normal. This implies that acidosis does not just affect the enzyme kinetics of coagulation (which should theoretically resolve when pH resolves) but rather induces some irreversible changes in clotting factors. One of those changes may be fibrinogen degeneration. One similar study also gave pigs acidosis with IV hydrochloric acid. In the study, acidotic pigs had decreased fibrinogen, without any accompanying increase in fibrin synthesis. Furthermore, there was no increase in D-Dimer, a by-product of fibrin clot formation. This was evidence that acidosis decreases fibrinogen by breaking it down, rather than converting it into a clot.

Acidosis also disrupts platelet function at several levels. An extensive study from 2012 measured platelet aggregation at both normal pH (7.4) and lower ones (7.0 and 6.5). αIIbβ3 integrin, the surface protein that platelets use to bind to each other, changes conformation at lower pHs. In addition, Ca2+ channels in both platelets and thrombin (the coagulation cascade factor that activates platelets) are impaired, which leads to less dense granule secretion by platelets and overall less platelet recruitment to form plugs.

Regardless of the mechanism, acid is clearly the enemy when it comes to hemostasis. However, because PPIs only work on gastric parietal cells, they will only be helpful in areas like the stomach and first parts of the duodenum where gastric acid may be affecting the pH around a bleeding vessel. Ulcers are the most notable victim of gastric acid, but there are other etiologies of UGIB. For example, one study from China gave patients with bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy either octreotide, vasopressin or omeprazole. Omeprazole was almost as effective as vasopressin (59% vs 64%) in controlling bleeding.

For something like esophageal varices, on the other hand, PPIs will do little good because those form above the stomach, and therefore need pressure reduction or banding to reduce bleeding, rather than acid suppression. Some studies have even shown that PPIs may actually increase the risk of lower GI bleeding by pH-induced alterations in gut flora that lead to inflammatory changes in the mucosa.

In cases where the etiology and/or location of a GI bleed is unclear, is waiting to initiate PPIs until after endoscopy acceptable? A Cochrane meta-analysis addressed this very question and showed that in terms of patient-centered outcomes like re-bleeding and the need for surgery, starting the PPI before endoscopy doesn’t provide any significant benefit. However, PPIs did reduce stigmata of bleeding when administered before endoscopy, and overall reduced the need for endoscopic therapy. This aligns well with the larger takeaway from this episode: IV PPIs can be effective hemostatic agents during acute UGIB and clinical judgment is needed to determine if they are needed or not.

Take Home Points

- The majority of upper GI bleeds are caused by ulcers, and the majority of ulcers are the result of gastric mucosal damage from H. Pylori or NSAID use.

- The acidic conditions of the stomach and duodenum impair clotting ability through inhibition of platelet and coagulation factor function.

- IV PPIs are primarily used to aid hemostasis for acute bleeding in acidic areas.

Listen to the episode!

Reboot! Bendopnea – The Curious Clinicians

Watch the episode on YouTube! [to be released]

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Sponsor

Freed is an AI scribe that listens, transcribes, and writes medical documentation for you. Freed is a solution that could help alleviate the daily burden of overworked clinicians everywhere. It turns clinicians’ patient conversations into accurate documentation – instantly. There’s no training time, no onboarding, and no extra mental burden. All the magic happens in just a few clicks, so clinicians can spend less energy on charting and more time on doing what they do best. Learn more about the AI scribe that clinicians love most today! Use code: CURIOUS50 to get $50 off your first month of Freed!

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Giancarlo Buonomo

◾️Show notes written by Giancarlo Buonomo and Tony Breu

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Buonomo G, Breu AC, Cooper AZ. Pumping Protons, Pumping Blood. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. July 10, 2024.

Image Credit: yayimage

One thought on “Episode 93- Pumping Protons, Pumping Blood”