Why can systemic pulmonary vasodilators worsen hypoxemia in COPD-associated pulmonary hypertension?

You can watch this episode on our new YouTube channel here!

Medicine is, if not simple, at least logical most of the time. If a patient is dry, give them fluids. If they’re wet, diurese them. If they have a platelet plug blocking one of their coronary arteries, give them some aspirin to prevent more platelets from getting stuck there. On this episode of The Curious Clinicians, we discuss an instance where medicine feels illogical. Many patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) have pulmonary hypertension (PH), where their pulmonary vasculature resistance is elevated. Then why do we avoid giving these patients systemic pulmonary vasodilators?

In COPD, the alveoli and their supporting architecture are gradually destroyed, such that portions of the lung have poor ventilation. The blood vessels of the lung (some of which also get destroyed along with alveoli) are unique in that when the mitochondria of vascular smooth muscle cells sense hypoxia, they induce vasoconstriction rather than vasodilation. This helps limit blood flow to oxygen-poor alveoli, and therefore brings the lung to a more favorable ventilation/perfusion ratio (V/Q ratio). In a self-limited case of V/Q mismatch (like pneumonia), the vasoconstriction is also transient. COPD is a chronically hypoxemic state, and the resulting longstanding vasoconstriction is one mechanism that can lead to vascular remodeling and persistently elevated pulmonary pressures. One could think of this vasoconstriction like an antalgic gait in someone with knee osteoarthritis –– helpful in the short-term, but leading to long-term problems in other joints.

When pulmonary pressures are high, strain is placed on the right ventricle. Over time, this can lead to cor pulmonale (right-heart failure from pumping against increased pulmonary pressures). Wouldn’t a pulmonary vasodilator help prevent this? In one 2010 study, researchers gave COPD patients who had PH either 20 or 40mg of sildenafil (a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor and pulmonary vasodilator) and then measured their mean pulmonary artery pressures (mPAP) at rest and after exercise. Compared to their baseline, the subjects experienced an average 6 mmHg drop in mPAP at rest and 11 mmHg after exercise.

The researchers also measured the PaO2 and V/Q distribution (the LogSD Q in the graph above). As mPAP decreased, V/Q matching and PaO2 decreased simultaneously. Far from improving oxygenation, the pulmonary vasodilator actually worsened it. Knowing what we know about hypoxic vasoconstriction, this actually makes sense. Although ultimately maladaptive, vascular remodeling helps divert blood away from the poorly-ventilated lung areas (in COPD from smoking, most often the apices) and into the better-preserved ones. A vasodilator removes this ability to selectively divert blood flow, leading to perfusion of oxygen-poor lung areas and worsening hypoxemia. Another study from 2012 extended the sildenafil treatment out to four weeks and saw similar results –– no improvement in subjects’ 6-minute walk distance and worsened blood oxygenation and symptoms.

The use of systemic vasodilators is subject to the same counterintuitive logic behind a conservative approach to supplemental oxygen in COPD. O2 is an absolute necessity in the care of certain COPD patients, as the landmark NOTT trial in 1980 showed that continuous oxygen therapy resulted in lower mPAP, improved oxygenation, and lower mortality than in nighttime-only therapy. Supplemental O2 helps to optimize oxygenation in alveoli with poor ventilation, and some vasodilation helps the blood pick up that O2. However, an overly generous O2 flow in patients with advanced COPD can dilate the constricted vasculature so much that it perfuses areas full of trapped CO2, leading to increased dead space, hypercapnia, and somnolence.

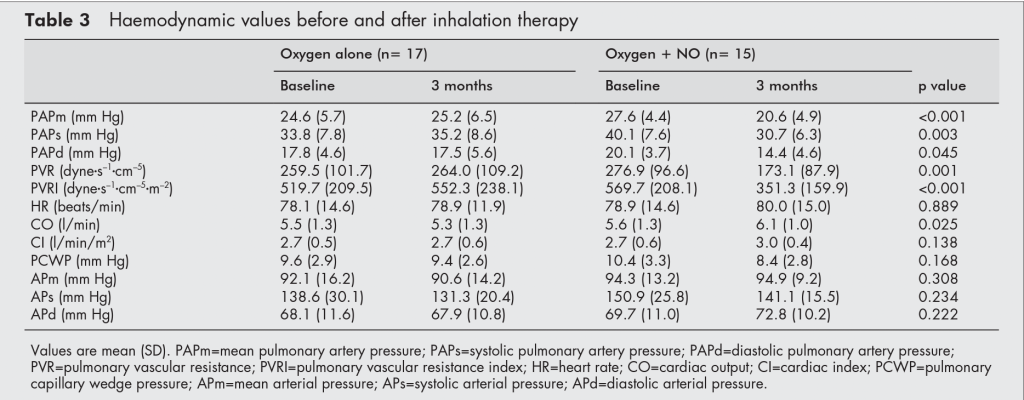

There is a way around this. Systemic vasodilators are counter-productive because they do not distinguish between areas with good and bad V/Q ratios. However, inhaled vasodilators should reach the best-ventilated areas and, therefore, preferentially dilate the vasculature there. A 2003 study from Austria confirmed this. Forty patients with COPD received either continuous supplemental O2 or O2 mixed with nitrous oxide (NO), a pulmonary vasodilator. After three months, the NO group not only saw an average 7mmHg drop in mPAP but a 0.5L improvement in cardiac output. Unlike sildenafil, inhaled NO caused no significant change in PaO2. Further investigation has shown that iloprost, a short-acting prostacyclin analog and pulmonary vasodilator, lowered mPAP and improved exercise tolerance after inhalation, while maintaining oxygenation.

While inhaled vasodilators are not a mainstay COPD therapy at this time, the INCREASE trial from 2021 showed that inhaled treprostinil (a longer-acting prostacyclin pulmonary vasodilator) improved exercise capacity in patients with PH from interstitial lung disease (ILD) while maintaining oxygenation. This led to the FDA approving inhaled treprostinil for ILD-related PH.

Take Home Points

- Hypoxic vasoconstriction is the main cause of pulmonary hypertension associated with COPD.

- In this situation, systemically administered pulmonary vasodilators can worsen V/Q matching and, therefore, can exacerbate hypoxemia, even while lowering pulmonary arterial pressures

- Inhaled pulmonary vasodilators appear to be safer in this situation, though there is better data for inhaled treprostinil in patients with PH associated with interstitial lung disease. This now has FDA approval for that indication.

- Plain old supplemental oxygen is an important therapy in hypoxemic patients with COPD and brings down pulmonary vascular resistance by minimizing maladaptive hypoxic vasoconstriction

Listen to the episode!

122 – When CRP Goes Missing – The Curious Clinicians

Watch the episode on YouTube!

Link to Related Tweetorial

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Sponsor

This episode is sponsored by Cozy Earth. Use code CURIOUS for 35% off at cozyearth.com, and embark on your travels in comfort!

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Avi Cooper

◾️ Show notes written by Giancarlo Buonomo and Avi Cooper

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Cooper AZ, Abrams HR, Breu AC, Buonomo G. Shunting a Mismatch. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. May 1, 2024.

Image Credit: Thoracickey.com