Did ancient civilizations discover antibiotics?

We can all agree that modern medicine is “advanced,” however a vague term that may be. We can, with relative ease, image the deepest parts of the body, identify and treat innumerable pathogens, and use machines to keep people alive even when their kidneys, hearts, and lungs are failing. It’s hard to imagine practicing medicine (let alone being a patient) centuries ago when now routine things like albuterol for asthma or an EKG for chest pain were not yet around. Here’s a humbling thought: In a few hundred years, won’t people talk about how primitive and ignorant medicine used to be in 2024? It makes you wonder whether we should so quickly discount the medical capabilities of our ancestors. In this episode of The Curious Clinicians, we investigate whether ancient civilizations actually knew about something we regard as a triumph of modern medicine: antibiotics.

We can’t discuss this topic and not begin with physician and microbiologist Alexander Fleming, the discoverer of penicillin. Although most famous for his groundbreaking discovery in 1928, Fleming actually made his first important antimicrobial discovery in 1921, while at St. Mary’s Hospital, London. A notoriously messy scientist (more on that later), Fleming discovered one of his agar plates was contaminated with bacteria. Fleming had a cold and decided to add some of his mucus to the plate just for grins. Two weeks later, he and his assistant noticed the mucus had killed off a section of bacteria. “This is interesting,” mused Fleming, and he proceeded to test various bodily fluids, including his laboratory staff’s tears, and found they all had anti-bacterial properties. They named this mystery compound lysozyme, which we now know to be an antibacterial enzyme that’s part of the body’s innate immune system.

Fleming would later claim that he deliberately kept his office messy, in case something ‘interesting’ might happen, as it did with lysozyme. In 1928, he left an agar plate of staphylococcus out when he went on vacation. When he returned, there was a small spot of penicillium notatum mold on the agar, and a clear ring of no bacteria growing around it.

Fleming surmised that there was a bactericidal “mold juice” being secreted. For the next several years, his lab attempted to purify this substance, but it proved difficult. Even when the lab published its initial findings, penicillin was presumed to be more useful as a laboratory tool rather than as a clinical antibiotic. This did not stop several clinicians from giving un-purified penicillin (apparently successfully) to patients throughout the 1930s, although the results were not published at the time.

In 1939, researchers at Oxford developed methods for purifying large amounts of penicillin sufficient for clinical trials. The next year, they showed that penicillin could protect mice against streptococcus infection. The first human to get this Oxford penicillin was a 43-year-old policeman named Albert Alexander, who in 1941 was desperately ill with abscesses in his face, neck and lungs. Some claim he got them from a rose-thorn scratch while working in his garden; others say he was wounded in a bombing. Regardless, he got several injections of penicillin and seemed to be making a miraculous recovery … until the supply ran out and he passed away. Production would ramp up throughout WWII as it became a battlefield necessity, and after the war, antibiotics became a staple around the world.

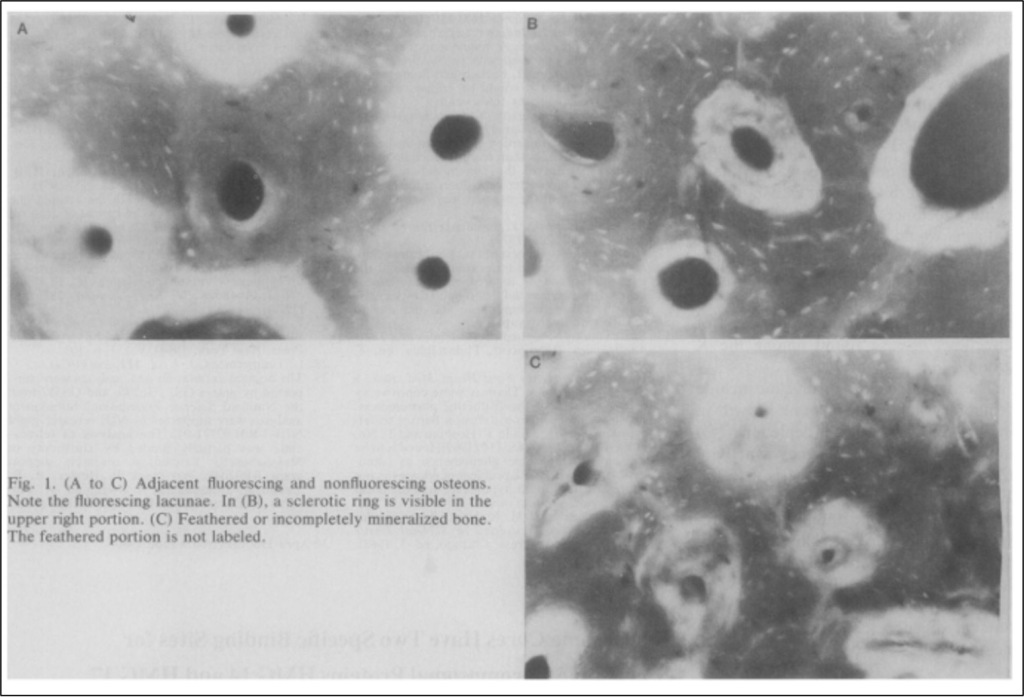

It took a huge amount of time and research to make penicillin a clinically useful product. It seems implausible to think that ancient civilizations could have done something similar. But penicillin was discovered serendipitously. Could ancient civilizations have made similar insights? In 1980, an anthropology paper studied bones from a cemetery belonging to the Nubian culture of North Africa. The bones were from around 350 CE and had been naturally mummified. Under a fluorescent microscope, the bones had the same pattern one sees in the bones of someone exposed to tetracycline antibiotics (a yellow-green fluorophore under 490 angstroms of UV, to be precise).

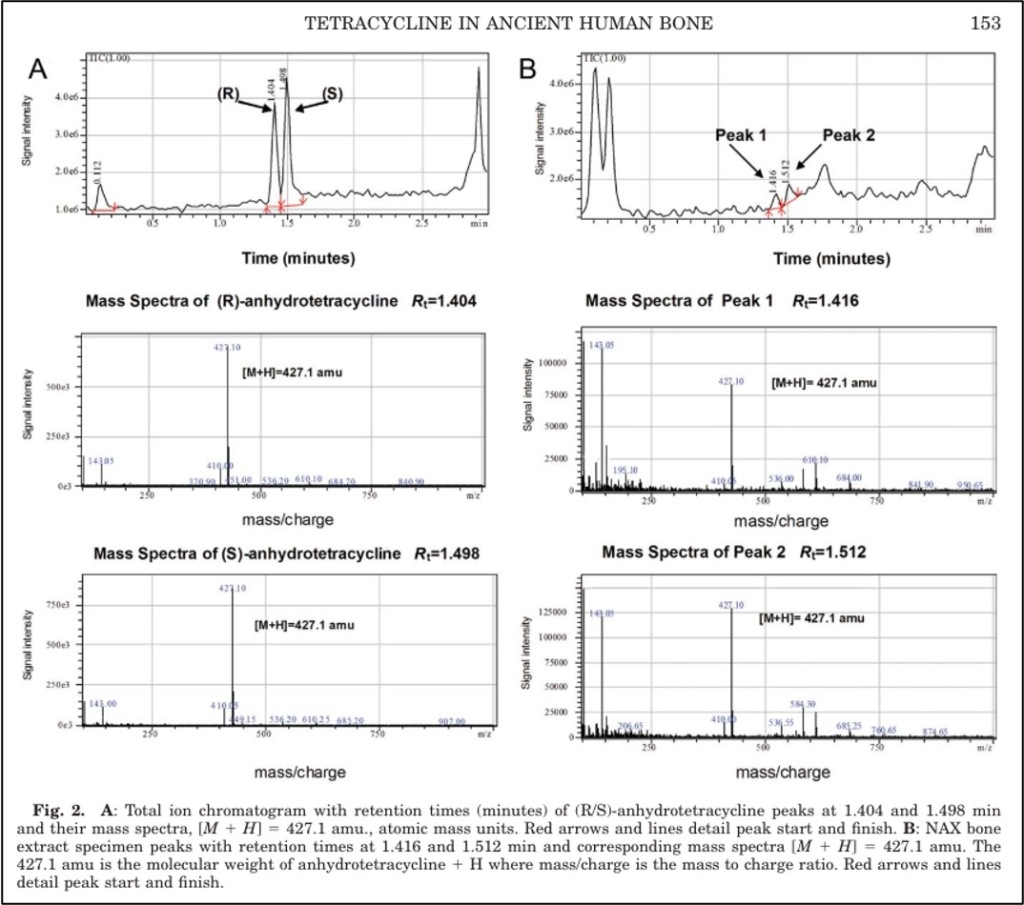

Tetracyclines are ion chelators and bind the calcium in bone, particularly developing bone (one of the reasons they are avoided in pregnancy). The Nubians were apparently exposed to large amounts of tetracyclines throughout their lives, possibly even at therapeutic levels. When this result was first published, it was met with skepticism, with some claiming the fluorescence was just from post-mortem bacterial and fungal infiltration. However, thirty years later, another group studied the bones using mass spectrometry and confirmed there were high levels of natural tetracyclines in them.

The big question, of course, is how those tetracyclines got in there? We can’t know for sure, but the leading theory is that the Nubians stored grain in mud bins, which allowed streptomyces, a bacteria that naturally produces tetracyclines, to flourish. When this grain was used to make bread and beer, the Nubians would ingest the antibiotics. There is evidence to support this – soil from the part of the Sudan where the Nubians lived has tetracycline-producing streptomyces in it!

One wonders, of course, whether the Nubians “knew” what they were doing. It can be argued that if beer and bread were staples of their diet, there’s no way to separate out the intentional and the incidental. Several authors on both the 1980 and 2010 papers have argued that even if these people didn’t understand the mechanism, the high levels of tetracycline in the bones of so many people across the population, including children, implies deliberate ingestion. Streptomyces gives off a golden hue, and one could imagine the Nubians looking at their glowing beer and thinking it was something special.

Take Home Points

- The effects of antibiotics may have been known in some fashion by an ancient North African civilization called the Nubians

- This theory was based on the consistent discovery of high amounts of natural tetracyclines in mummified bones from that population across all age groups and in high amounts, suggesting consistent exposure

- This natural tetracycline was likely produced by streptomyces bacteria when the Nubians processed and fermented grain

Listen to the episode!

91 – Ancient Antibiotics – The Curious Clinicians

Watch the episode on YouTube!

CME/MOC

Click here to obtain AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™ (0.5 hours), Non-Physician Attendance (0.5 hours), or ABIM MOC Part 2 (0.5 hours).

As of January 1, 2024, VCU Health Continuing Education will charge a CME credit claim fee of $10.00 for new episodes. This credit claim fee will help to cover the costs of operational services, electronic reporting (if applicable), and real-time customer service support. Episodes prior to January 1, 2024, will remain free. Due to system constraints, VCU Health Continuing Education cannot offer subscription services at this time but hopes to do so in the future.

Sponsor

This episode is sponsored by Cozy Earth. Use code CURIOUS for 35% off at cozyearth.com, and embark on your travels in comfort!

Credits & Suggested Citation

◾️Episode written by Avi Cooper

◾️Show notes written by Giancarlo Buonomo and Avi Cooper

◾️Audio edited by Clair Morgan of nodderly.com

Cooper AZ, Abrams HR, Breu AC, Buonomo G. Ancient Antibiotics. The Curious Clinicians Podcast. June 12, 2024.

Image Credit: Science Museum